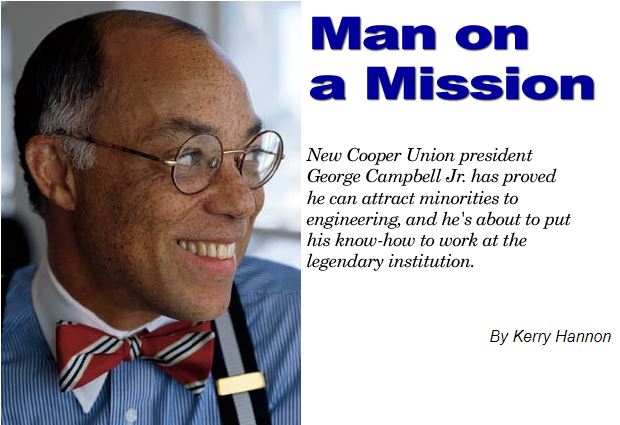

Sep 2000 – George Campbell, Jr.

You learn a lot about people by listening to the way they talk. So when you have a conversation with George Campbell Jr., the new president of New York’s Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, you know more about this guy in 15 minutes than you probably know about your cousin. There’s the speed, the intensity, the passion. In fact, he has so much to say that it’s a challenge to lob a question his way.

But what you really know at the end of the nearly three-hour conversation is that Campbell, 53, who has a bachelor of science degree from Drexel University and a Ph.D. in theoretical physics from Syracuse University, is a master problem solver. And that’s something the 141-year-old Cooper Union, founded in 1859 by Peter Cooper, a prominent industrialist, desperately needs. Until now, the school has been careening into this new century with cramped, aging buildings; an antiquated curriculum that, by all accounts, has not kept pace with the rapid growth in high-tech areas like e-commerce; and a student body that is predominantly white, although the school is situated smack dab in a metropolitan community that consists of roughly 80 percent minorities.

From a diversity standpoint, the numbers aren’t good. Of the 900 sutdents at Cooper today, minority enrollment makes up 14 percent. That translates to 6 percent African American and 8 percent Latino. Cooper, who founded the college with the purpose of prohibiting racial discrimination in enrollment and offering free education to every student, would surely be dismayed.

Another Barrier Broken

Campbell, though, is determined to dramatically change that course and return to Cooper’s vision. It took the Cooper Union board members about four months to select Campbell, then president and chief executive officer of the 25-year-old National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering (NACME), a non-profit corporation also based in New York, as the school’s 11th president. He is also a former research manager at AT&T Bell Labs, one of the country’s leading research institutions.

Aside from his top-rate credentials, perhaps the most significant aspect of Campbell’s appointment is that he is Cooper’s first black president since its founding. Campbell, a resident of Harlem, was hand-picked from a field of seven applicants to replace John Jay Iselin, who resigned in April after a decade in the position. Campbell’s appointment was a signal to the black community that another barrier had been penetrated. “There has been a huge outpouring from the black community,” he says. “I’m fortunate to have been able to have the education and preparation to succeed. There are not enough black people who have had that opportunity, and I want others to have it.”

At a critical time when this country’s colleges and universities are clawing to attract more minority students to engineering, Campbell couldn’t have been more suitable for the job. “He had it all,” says Milton Glaser, a graphic artist and vice chairman of Cooper Union’s board. “He had a background in the science world, a love of the arts, and a decency and balance about him. But finally, it was just the force of his personality.”

And that he has. Campbell is not short on ego. “The board saw me as visionary,” he says. “I think that is my responsibility. It’s the responsibility of any leader to think about where the future is going and to reflect on it,” he says confidently.

What does he see? In two words, monumental change. “We need to rethink ourselves. We need to reinvent the school,” he boldly proclaims. That would be no small feat with such an entrenched institution.

Building Diversity

But Campbell has the track record to suggest that he can pull it off–if not overnight, then in due time. For the past 11 years, the bespectacled, bow-tied Campbell has presided over NACME, the nation’s largest privately funded source of scholarship money for minority students in engineering. Donors include IBM, Lucent Technologies, and Xerox Corporation, among other big-name corporations and foundations. Campbell’s mission at NACME was to urge more minority students to pursue a career in engineering. He did.

Since its inception, NACME has helped produce more minority engineers–who attended hundreds of colleges around the country including such universities as Stanford, Rice, and Harvard–than any other organization in the country.

Since 1980, the group has provided scholarships for more than 7,000 students–10 percent of all minority engineering graduates. The organization has had a 92 percent student retention rate, compared with 37 percent for minorities and 67 percent for engineering students nationwide, and the average grade point average is 3.2. Even better–in some respects–he was a key force in the group’s 82 percent revenue growth from 1996 to 1999 when revenues reached $9.5 million. Meantime, contributions reached $8.2 million last year, up from $6.6 million a year earlier. “We could never have accomplished that growth without George.” says Nicholas Donofrio, an IBM senior vice president and NACME’s chairman.

Bolstering college and university rosters with minority students is a genuine passion for Campbell. Only 10 percent of students nationwide who received bachelor’s degrees in engineering last year were African American, Hispanic, or American Indian, according to Campbell. “That’s not right,” he says with a quiet, steady, but determined voice that is tinged with a hint of disgust. “Colleges and universities across the country have got to do more to draw minority students into the engineering field.”

Campbell’s tenure kicked off in July when he set up shop on Cooper’s East Village campus, which houses its three professional schools–architecture, art, and engineering. As early as April, though, he was already spending vital chunks of his mental and physical energy focusing on his new challenges and Cooper’s dilemma.

What attracted Campbell to the college? First, Cooper Union has a reputation for being at the forefront of social reform, even if today that aura has faded somewhat. Its Great Hall Stage was the platform for some of the earliest workers’ rights campaigns and for the birth of the NAACP, the women’s suffrage movement, and the American Red Cross. Cooper Union is the only private, full-scholarship college in the U.S. dedicated exclusively to preparing students for the professions of engineering, art, and architecture. “For the most part, I came here because its program focuses on the two disciplines that are very dear to me,” he says. It’s the confluence of science and art. With the explosion of new media and the Internet, there is an increasing amount of collaboration between artists and scientists. That’s the future.”

And Campbell is no stranger to Cooper. For the last five years, he has served on the advisory council for the school of engineering and is well aware of the myriad changes needed to get Cooper back on its feet, both academically and financially. Cooper needs to be transformed in much the same way as NACME was over the past decade. Campbell desperately wants to expand the pool of minority students studying engineering and succeeding, and to rebuild the school’s resources.

Shaking the Money Tree

Ratcheting up efforts to raise funds for the school is a major priority. Cooper is currently running a significant deficit, according to Campbell, although he would not elaborate on just how much red ink is flowing. “I think we can solve it very quickly,” he says. And based on his success at NACME that seems quite possible.

Campbell is a born fund-raiser and well connected in New York art circles. He has an extensive African art collection that runs the gamut from paintings to steel sculptures to ceremonial masks. His wife of 31 years, Mary Schmidt Campbell, an art historian, is the dean of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and was a commissioner of cultural affairs during New York Mayor Ed Koch’s administration. The couple has been a fixture on that social scene for years, and their involvement has reaped its rewards.

Campbell’s arrival signals a big change for the Cooper culture, because the college has not historically focused on fund-raising. In essence, it has been lucky enough to get by tapping into its healthy endowment to keep the school afloat and student tuition paid in full. Until now, that is. Cooper does still have significant real estate holdings, including New York’s famous Chrysler building and blocks of land in the East Village. But the cost of running operations has ballooned over the past decade, and the school has not had the resources to retain quality professors, improve a deteriorating infrastructure, and cover the rising costs of tuition.

Clearly part of Campbell’s appeal to the Cooper board was his knack for fund-raising. While at NACME, he spent more than 55 percent of his time on the road, getting donors to fill the organization’s coffers. So Cooper alums can brace themselves for an onslaught–Campbell doesn’t like to take no for an answer. Next year, he’d like to increase the $36 million budget. And to do this, Campbell will have to engage in additional fund-raising; the school currently attracts $7 to $10 million annually.

The Vision Thing

So what’s the master plan at this early stage? First, Campbell wants to redesign the school’s physical facility. The campus buildings are woefully inadequate, dating to the 19th century. He wants to expand the campus with more efficient space–not a cheap plan in the tight New York real estate market.

At NACME, Campbell was instrumental in initiating the Vanguard program, which not only identified potential scholarship students, but helped ensure their success. The program included a 10-hour series of workshops aimed at strengthening thinking skills, creativity, persistence, and motivation. “These students have to make up for a great deal in a short period of time,” he says.

Campbell’s team targeted inner-city schools. The students were observed for their leadership skills as they went through the workshops, and then interviewed one-on-one. Those who were selected for scholarships underwent a summer preparation course in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. “It’s not hard to identify students,” he says. “The hardest part is getting them up to speed.”

Now, as he did at NACME with the Engineering Vanguard Program, he wants to put more resources into identifying inner-city kids inclined toward math and science careers at the high-school level so they can get the right preparation. He hopes to partner with the New York City Board of Education, enlisting their help with the effort. “The attributes of a successful engineer have little to do with SAT scores or grade-point averages,” he says.

He wants to change the way the school evaluates potential students. In the past, it has relied on academic achievement to determine its future students. However, there is a huge disparity between the number of math and science teachers in minority communities versus non-minority communities, explains Campbell. The new process would involve interviews and various seminars. “It’s not about changing admission standards,” he asserts. “I am not talking about giving any students preferential treatment. Cooper will still be pure merit-based.”

Then there is the enormous task of redesigning the school’s curriculum, an area where he is sure to meet some resistance from the old-line faculty. In terms of the engineering department, Campbell wants to focus efforts on a curriculum that teaches students how to make the best use of the Internet, in particular. To date, he and his team are still putting together their outline and specifics were not yet available.

“Things are moving so slowly,” Campbell laments, and he hadn’t even officially started his post at the time of this conversation. This is a guy who wants to make things happen, fast. But it’s hard to re-engineer an aging institution, particularly one so steeped in tradition.

“I’m not a top-down manager,” he says. “I like to build consensus, but the faculty has to realize that the buck stops here. I can’t make everyone happy. I have to make the decisions and do the right thing so that the institution doesn’t stagnate.”

Campbell’s credo: It’s all about solving problems. “Engineering is solving problems. Math is solving problems. Physics is solving problems. Architecture is solving problems. Art is solving problems.” Now he’s got himself a whopper to solve.

Kerry Hannon is a freelance writer living in Washington, D.C.

Cooper’s Pioneering Dean

Eleanor Baum, dean of engineering at Cooper Union, will laugh when she reads this, but she reminds me of my mother. She has just dashed away early from a fancy luncheon in downtown Manhattan where she was rubbing shoulders with the Mayor and other high-powered New Yawkers, and what she really wants to know, after being stuck in mid-town, mid-day traffic, is how I am doing after my recent fall from my horse. Now here is a woman, age 59, who is at the top of her field. She’s the first female dean of an engineering school anywhere, and she wants to talk about my neck injury.

Baum, who came to Cooper Union 12 years ago as the dean of engineering, is a pioneer in her field. Today, there are 10 female engineering deans at ASEE-member schools. That’s up from seven a scant four years ago.

Baum, an electrical engineer by training, has earned a reputation as one of the most outspoken voices for bringing women into the engineering world, and she has the numbers to back her efforts up. Today, one third of Cooper’s 400-plus engineering students are women. When she arrived, that figure was closer to 20.

Recruiting women engineers has been her internal marching orders since the day she settled into her Astor Place office. “Basically the lack of women in engineering programs is due to the image of engineers,” she says. “We’ve done a lousy job of describing who we are and what we do. What engineers do is solve problems to make life better for people.”

Baum has vivid memories of her 1950s Midwood High School days in Brooklyn when she was the only girl taking advanced math and science classes. Her girlfriends were all chattering about getting married. “People thought I was weird,” she recalls. Then, at the engineering school at City College in New York, she found she had to use humor rather than anger to deal with the male image of an engineer–and occasional harassment from her male professors and counterparts.

So what’s it like being such a high-profile dean? “Being a dean is like parenting,” says the wife of a physicist and mother of two daughters (neither an engineer) and two granddaughters, who she is still recruiting. “It takes people skills, communication skills, and management skills.”

Having George Campbell in the top seat can only bode well for her prestigious department. “He has a background of innovation and of creating partnerships which will be useful,” says Baum. “We want to enhance the education of our students and that takes money.”

“And by the way,” she says at the end of the interview, “go see a doctor about that neck pain and promise me you will let me know what he says.” –KH

Category: Action Man