October 2009 – Feature

BY MARGARET LOFTUS

ALL IN THE FAMILY

To reach the next generation of engineers, involve the parents, too.

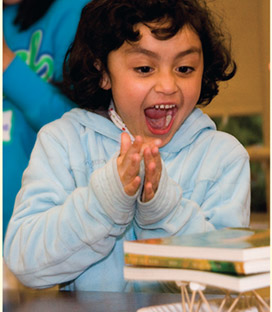

After participating in a recent K-12 engineering workshop, Emma Sarazin stopped to examine a soda machine, pondering how it worked. Just a few weeks earlier, the 10-year-old had only the vaguest idea of engineering – “something to do with cars.” But now she might even consider it as a future career. Tina Sarazin, who joined her daughter for the family program, was impressed: “I knew Emma would enjoy it, but I was surprised at how much it made her stop and think.”

From LEGO® engineering to robotics clubs, outreach programs for K-12 students in STEM activities rarely have required much of parents beyond chauffeuring and the occasional fee. But now that’s changing, thanks to a movement that sees parent involvement as key to solving the U.S. engineering crisis.

Predicated on the influence many parents have on their children’s career choices, “family engineering” joins parents and their elementary-age kids with faculty and students, and, often, professional engineers, to work on basic hands-on projects designed to spark interest in engineering. Introducing STEM activities early on is crucial to expanding the ranks of engineers, proponents believe, since the path to the advanced high school math courses required by most engineering schools is often begun when children are still in elementary school. By including parents in these activities, that interest is more likely to be supported down the road. “The number one thing we can do as engineers is convince parents that engineering is a viable thing for their children,” argues Elizabeth Parry, project director for RAMP-UP (Recognizing Accelerated Math Potential in Underrepresented People), an outreach program at North Carolina State University that includes family STEM activities. “If we don’t, we’re not going to get more kids into engineering.”

Defeating Stereotypes

Science learning as a family affair is nothing new. The Lawrence Hall of Science, a public educational resource center at the University of California, Berkeley, introduced family math nights in 1981. The goal was to render math less intimidating and more fun for children – but also for their parents, who often unwittingly pass on their own trepidations when asked for homework help. Common refrains like “I’m no good with numbers” or “Ask Dad for help” reinforce racial and gender stereotypes, say educators. “We wanted to convince parents that just because they might not have done well in math, that didn’t mean their child couldn’t do well,” says José Franco, director of Lawrence Hall’s EQUALS science programs. “There’s no such thing as the math gene.” The events were a big hit: Surveys found that participants enjoyed math more, and some parents even went on to pursue more education as a result. Today, Lawrence Hall offers a wide range of family programs in math, chemistry, physics, and animal sciences.

Still in its early days, family engineering has cropped up at a handful of schools nationwide, including North Carolina State, Rutgers University, and Marquette University. Other organizations have joined in, as well. NASA teams with the member schools of its Science, Engineering, Mathematics, and Aerospace Academy to sponsor STEM education Family Cafés. Since 2003, the Engineers Week Foundation has sponsored a Family Day at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., each February, providing hands-on engineering activities for over 6,000 participants.

One of the more ambitious efforts is being launched at Michigan Technological University, where the National Science Foundation has funded a three-year project to develop an activity guide, training workshops, and a website based on the school’s own popular family engineering nights. ASEE and the Family Science Foundation in Portland, Ore., have signed on to help disseminate the program’s materials and encourage the family model among engineering societies, student chapters, and engineering professionals. Field-testing of the program begins next year, which is slated to debut nationally in 2011.

Geared toward first through fifth graders, most family engineering programs operate on the principle that materials should be readily available in any household. A recent evening at Michigan Tech demonstrated how a water-saving showerhead works using 8-ounce plastic cups, push pins, a sharp pencil, and water. Venues tend to be informal settings outside the classroom, such as museums, libraries, and even churches.

Programs typically open with a series of simple activities drawn from various engineering disciplines, intended to instantly grab kids’ attention. After several openers come one or two longer projects, such as building a gravity-fed “hot chocolate machine.” But before the families launch into their activity, the evening’s facilitator reviews some basics, reminding the budding mechanical engineers that water flows downhill, for example. They also get a rundown on design principles and are advised to follow five simple steps: ask; imagine; plan; create; and improve. “We’re trying to simulate the engineering process,” notes Neil Hutzler, the director and principal investigator on the Michigan NSF project. “They really have to think about it.”

Whether it’s the thrill of building a pyramid or a love of hot chocolate, the challenge strikes a chord with kids. After creating a prototype with her father and younger sister, 7-year-old Olivia Hohnholt was determined to perfect her design, says her father, Christopher. “The minute she got home, she was grabbing paper cups out of the bathroom. I foresee many spilled cups of water.”

Parents are often more reserved than their charges – but only at first, says David Heil, director of the Family Science Foundation and another Michigan Tech project investigator. “When the families arrive, children immediately rush up to the table, and parents stay in the background. But pretty soon, they’re looking over their kids’ shoulder, and then in a matter of 5 to 10 minutes, the parents and kids are deeply engaged and talking to other families across the table.”

Often, the adult learning is just as important as the child’s. “Most parents are not scientists, and most kids are natural scientists,” Heil notes. So the evening “provides them with an opportunity to interact in a way they wouldn’t otherwise. The role that the parent plays is not coach, but of a co-learner.” The fun factor can’t be underestimated, says Heil: “It loses its relevance when it becomes a class period instead of hands-on.” After all, the intent is not so much to teach engineering principles as it is to stimulate interest.

Another core element is the participation of undergraduate engineering students and professionals. “For the most part, kids are pretty much unaware of engineering as a career,” says Joan Chadde, K-12 education and outreach coordinator at Michigan Tech. In some cases, engineers conduct the session; but more often, they’re on hand to discuss what they study or do for a living. And so far, there has been no shortage of volunteers, says Chadde: “They like the idea of getting someone else excited about engineering.”

Opening Doors and Minds

Educators know that role models are important and so, seek to find professional and student engineers from backgrounds similar to the kids’, and to include both men and women. “One of our missions here is to address gender and racial bias,” says Jack Samuelson, coordinator of engineering outreach at Marquette, where he puts on four- and five-day family engineering academies throughout the year. Often, “the worst offenders perpetuating these stereotypes are parents,” so that boys are encouraged to take up math and science, but girls are not. The same goes for underrepresented minorities, says Parry, which usually reflects parents’ misunderstanding of engineering.

But can one night make a difference? “I don’t know if you change their mind in an evening, but you can open a door,” argues Parry. “[Parents] are likely to see an ability they aren’t likely to see at home. It’s that powerful,” At the very least, Heil says, parents who participate may become more open to a child’s interest in engineering: “We’re trying to counter those moments where a kid starts eagerly talking about science or engineering, and the parent says, ‘Oh, I don’t know a thing about that.’”

For now, evidence of family engineering’s success remains anecdotal. “We’ve had numerous examples of parents commenting that the experience prepares their kids to learn in school,” says Heil. “The television is off, the homework’s done, and they are doing science and engineering together in a very fun and relevant way.”

And that could be the real key to family engineering. Once they’ve attended a session, moms and dads may begin to view their kids’ tinkerings as part of an emerging talent, not just a big mess. For children, new possibilities may start to come into focus. As Emma Sarazin enthuses, engineering is “kind of like doing arts and crafts because you get to experiment with everything.”

Margaret Loftus is a freelance writer based in Boston.

Category: Features