Bangalore-jolt

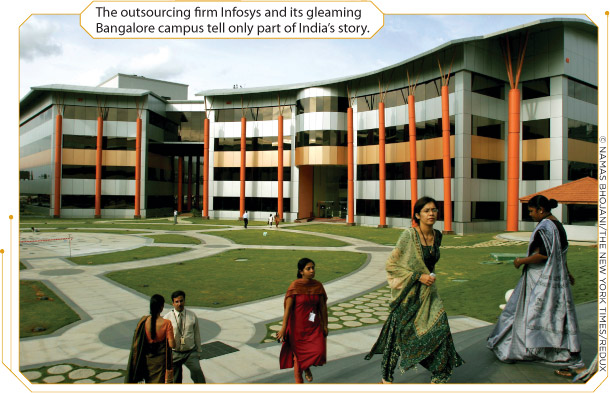

BANGALORE, India — To get a feel for the ambition coursing through this country’s high-growth, high-tech sector, take a ride south of here to Electronics City, a 330-acre industrial park known as India’s Silicon Valley. There, on a verdant, four-year-old campus, sits the Indian Institute of Information Technology Bangalore (iiit-b), a post-graduate university chaired by N.R. Narayana Murthy, founder of outsourcing giant Infosys Technologies Ltd.

Its modestly lowercase logo notwithstanding, iiit-b seeks to be nothing less than the Stanford of India. Funded by the state and private companies, including Motorola, it offers stimulating courses taught by tech luminaries and A-list professors, state-of-the-art classrooms and a theory-light, practice-oriented approach. Berthed on the second floor are innovation and incubation labs. Students in a software engineering class rave about the flexible curriculum and exposure to real-world tech.

“I’m dreaming of starting my own company,” says Raghuram Ashok, a 23-year-old software engineering grad student at iiit-b. A generation ago, such an aspiration would have been rare among young, educated Indians. “If you go back 25 or 30 years, just to get a job after graduation, even with good qualifications, you had to know the right people in the right places. It was very dismal,” notes institute professor S.S. Prabhu. But the IT boom “has unleashed a tremendous creative energy.”

Demand for Trained Talent

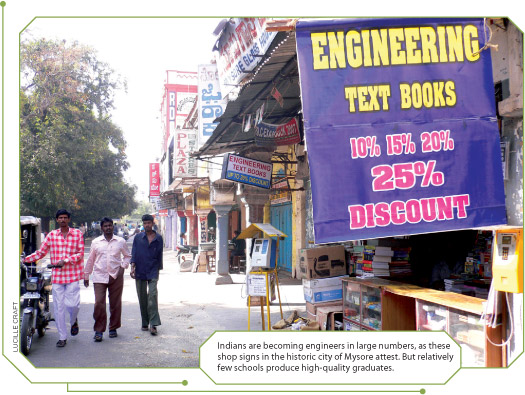

Yet therein lies a challenge. The institute is one of the players in a drama now unfolding on Indian campuses, many of them freshly planted, that could determine whether all this creative energy is properly tapped and channeled. In particular, the white-hot pace of expansion in the tech industry—an estimated 30 percent annually—has upended the once placid realm of engineering academia. And the escalating demand is not just for computer science and IT majors. The expanding economy is also fueling an infrastructure boom and increasing the need for civil, electrical and mechanical engineers. According to one professor, India has now reached a point where virtually anyone who wants to become an engineer, can.

But will he or she be any good? In addition to iiit-b, some 100 colleges and institutes have sprung up in and around Bangalore, and many more have spread across the subcontinent. All are engaged in an unprecedented real-time experiment: Can one of the world’s largest countries—but one that’s still developing—assemble a trained workforce at warp-speed?

The race to ramp up India’s institutions of higher learning is shadowed by a sense of impending crisis, a fear that the dearth of fresh engineers could short-circuit India’s IT juggernaut. At even the most prestigious corporations, human resource managers are worried. “We all have a shortage of manpower,” says John K. John, deputy general manager for “talent transformation” at HCL Technologies Ltd. Scarcely a day passes without the Hindu or Deccan Herald solemnly proclaiming that the country’s formidable tech industry will grind to a halt barring a drastic upgrade and expansion of technical education. Tirelessly playing the role of Cassandra is Kiran Karnik, president of the National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM), the chamber of commerce for India’s IT industry.

“While some young men, on the brink of starvation, desperately look for work, employers elsewhere look—with almost similar desperation—for appropriate persons to fill tens of thousands of vacancies,” Karnik recently remarked in London’s Financial Times. “The market is providing strong signals about the failure of our education system. It is not producing enough people with the skill sets our economy needs . . . . This could seriously stymie India’s economic growth.”

Though 464,743 engineering degrees were awarded in the 2004-5 period, according to the All-India Council for Technical Education, up from 401,791 the previous year, that rate of growth is still too slow. And too few qualified engineers are being produced. A joint study by the global accounting firm KPMG and NASSCOM warns that 235,000 jobs may be left unfilled by 2010 unless schools focus on quality as much as quantity.

Dire predictions notwithstanding, many experts remain sanguine. “It’s good to be paranoid,” says Sanjay Anandaram, founder and manager of the Jumpstartup venture fund. “It spurs people into action. The good news is, the people exist.”

“There is no dearth of engineering talent,” agrees Selvan D, senior vice president for talent transformation at Wipro. “It’s only in the right skills where the shortage is coming.”

Stark Contrasts Persist

India’s impressive strides over the past two decades can create a misleading impression, as it remains very much a developing nation. For every entrepreneurial hopeful like Ashok, there are many more working Indians who are left out of the IT story altogether. One out of every three ekes out life on less than a dollar a day. And while Indian companies have set the world standard for low-cost offshore business processing, citizens in rural regions still struggle without clean drinking water and electricity. At about 60 percent, adult literacy still pales beside China’s 90 percent. Indeed, two-thirds of the country’s engineers are schooled in just five states, all located in the more progressive southern region. In many cases, India’s institutions bring to mind a lumbering elephant, slow-moving and resistant to change.

A third of India’s one-billion-plus citizens are under age 15, so the question of how to steer more of India’s youthful and bountiful population into engineering is a crucial one. Yet it has only gained attention quite recently. India’s modern engineering educational system dates only to 1947, when the country gained independence and the republic’s education-minded first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, spearheaded investment in civil and mechanical engineering. Unfortunately, Nehru’s passion for pedagogy favored higher education at the expense of primary institutions and was aimed not at creating jobs and raising living standards but at constructing too many capital-intensive trophy public works.

The renaissance of India’s economy began in 1991, when the “License Raj,” a Soviet-inspired system of restrictive bureaucratic regulation, was partially dismantled. The move unleashed a tidal wave of investment by domestic and overseas firms and opened up India’s antiquated, hidebound economy to the world. Though oxcarts and beggars are still features of life, even in Bangalore, this tropical city of 6.5 million, once a balmy idyll where retirees spent their golden years, is now where Indians are making gold. As they redefine efficiency, these newly minted Bangalore entrepreneurs are remaking the face of modern business from Toronto to Tokyo to Toulouse. Every high-tech marque that matters has hung its shingle in this once somnolent pensioners’ paradise, from multinationals like Google, Yahoo!, IBM and Motorola to local outsourcing majors—Wipro, Infosys, HCL, Satyam and Tata—not to mention scores of lesser rivals. India’s success at training its low-cost workforce to serve as the call center and business-process “out-sourcerers” for overseas companies has transformed its economy into the second-fastest-growing in Asia, piling on an average 6 percent growth every year for the past 15.

Push for Engineering Education

The liberalization of India’s trade regulations not only energized business and gave Indians new confidence about competing on a global footing. It also injected fresh air and scale into the state university system, permitting for the first time the establishment of private colleges and institutes, some chartered by an astonishing range of homegrown luminaries. The SSN College of Engineering in Chennai (Madras), for example, was set up in 1996 by Shiv Nadar, the billionaire founder of tech giant HCL.

Until recently, quality higher education in engineering was guaranteed only to the precious few students who made it into the “tier 1” schools—the elite Indian Institutes of Technology and the Indian Institutes of Science, which award only about 3,000 undergraduate degrees a year. About twice as many four-year engineering students are taught at second-tier schools such as the National Institutes of Technology. The lion’s share of students are enrolled in tier 3 institutions. Most of these bottom-tier schools are private ventures less than a decade old, a product of what Indians refer to as their own perestroika.

Predictably, the feverish pace of college expansion has come at the expense of quality, and many tier 3 schools are, in fact, diploma mills, with no shortage of clientele. Anandaram, who has financed a number of tech startups, describes these schools’ appeal: “I’m a poor kid from some remote village, I see this flashy neon sign—‘This is your path to glory, all you need to do is pay me so much money, go through this six-week program and boom!’”

But uneven quality plagues even conventional four-year institutions. According to a widely quoted McKinsey Global Institute study, three-quarters of all engineering grads are unemployable, either because their training was too theoretical or outmoded or because of a lack of instruction in “soft” skills, which often translates to a poor command of English. India supports 18 official languages including Hindi, and only about 350 million Indians speak English as a second language.

In addition, when it comes to the teacher shortage, the IT industry is its own worst enemy. Industry salaries are so high that new bachelor’s holders can earn several times what their Ph.D. professors make. Understandably, precious few students can be coaxed into sticking around to earn postgraduate degrees. And Ph.D.s – forget it. Only a few hundred were trained last year. As a consequence, many schools must settle for teachers with only an undergraduate degree.

Aiming for the Top Tier

And yet, many of the upstart new private colleges have visions of attaining the standards of top U.S. schools. “All of us to some extent were influenced by MIT and Stanford,” says S. Sadagopan, the gregarious director of iiit-b. Sadagopan is something of a legend within Indian engineering circles, the archetype of a traditional Indian scholar whose modest demeanor belies a formidable academic career. He is also distinguished by his crimson caste mark, his habit of padding around barefoot and his apparently infinite memory for students’ names. Sadagopan despairs of the absence of a Stanford-style menu of majors at his own institution. “What we do not have are full-fledged liberal arts schools, a business school, a medical school—which would bring a lot more energy and dynamics” to the engineering school.

Just down the road from iiit-b is the Bangalore campus of the Amrita School of Engineering. In some ways a distinctly Indian enterprise, Amrita is financed by the foundation of Mata Amritanandamayi Devi, or Amma, a charismatic 54-year-old fisherman’s daughter. With only a fourth-grade education, she has gained international renown as a spiritual leader, popularly known as India’s “hugging saint.” Religion is not a requirement at Amrita, which offers majors in medicine, biotechnology and nursing, alongside courses in Ayurvedic medicine and yoga. But the founder’s humanist moorings have helped this engineering school lure back from California’s Silicon Valley a number of Indian luminaries, though it comes nowhere close to matching their previous salaries. They include P. Venkat Rangan, who founded and ran the University of California-San Diego’s multimedia lab until decamping for Amrita in 2003.

“If you’ve lived in the U.S. for 10 years, then you’ve made enough,” says Shekar Babu, another former expatriate on the Amrita faculty, who reportedly relinquished a salary about 30 times what he now earns for the chance to give back to society.

To increase the offerings at its multiple campuses in three states, Amrita has started giving selected classes on a high-bandwidth, interactive satellite E-learning network; it is also working on beaming lectures over an IP network.

“Today, education is highly interdisciplinary,” Rangan says. “We understand that to know physics, then you need to know how the eye perceives—biology—then electronics and computer science.”

A number of educators and working engineers suggest that India’s traditional experiential learning mode, in which students imbibe knowledge from a guru, makes many students uncomfortable with the virtual classroom. Educators at Amrita respond that virtual classes are intended to complement, rather than supplant, conventional classrooms. And the Amrita project, which has received high-level endorsement from the Indian government and is slated to tap faculty from more than a dozen U.S. engineering schools, appears to offer one strong possibility for overcoming the severe shortage of teaching talent in India.

Industry Invests in Education

| Finding Common Ground An Indian-reared U.S. professor spearheads a drive to boost engineering education in both his native and adopted countries. By Spencer Potter |

| India and the United States have a lot in common. Both countries are thriving—the U.S. being the world’s largest economy, India its most populous democracy. Both are built on pillars of tolerance and diversity.

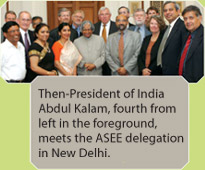

But in engineering education, the two nations differ sharply. U.S. schools view research and Ph.D. programs as the heart and soul of their departments, while educators in India cite lack of research as one of their most significant shortcomings. American engineering schools have trouble recruiting and keeping enough engineering students to meet domestic and international demand. For college-bound Indians, engineering is one of the most popular pursuits, but the degrees conferred at second- and third-tier institutions are of questionable quality. Krishna Vedula, professor and Dean Emeritus of Engineering at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, saw an opportunity for organized collaboration that would benefit both countries. Born in southern India, Vedula received his undergraduate degree from the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay, and came to the U.S. to pursue graduate work 37 years ago. ASEE has partnered with Vedula, providing him with the resources to realize his vision. After drawing an overwhelmingly positive response from other Indian-born U.S. deans of engineering, Vedula founded the Indo-U.S. Collaborative for Engineering Education (IUCEE). Together with ASEE, Vedula and his colleagues organized a two-part IUCEE Action Planning Session to advance the quality and global relevance of engineering education in India and the U.S. The first forum, held in June 2007 at the Infosys Mysore Campus Leadership Institute in Mysore, India, drew 81 education and business leaders from the two countries, along with government officials. Afterward, a delegation led by James Melsa, now ASEE president, visited New Delhi and briefed India’s outgoing president, Abdul Kalam—who has a degree in aeronautical engineering—and U.S. Ambassador David C. Mulford. A second forum, with more than 100 attendees, was held two months later at the National Academy of Engineering in Washington, D.C. It culminated with a $333,000 pledge to IUCEE by the Deshpande Foundation. Of particular concern to participants at both forums was the lack of interest in science and engineering in the U.S., the inadequate preparation of engineering graduates in India, the shortage of students pursuing Ph.D.s in engineering in India, and the need to encourage and support women and underrepresented minorities in engineering careers in both countries. Several promising models were considered worthy of large-scale implementation. The two sessions resulted in plans for an Indo-U.S. Engineering Faculty Institute with four areas of concentration: curriculum content and delivery, education quality and accreditation, research and development, and innovation and entrepreneurship. The Institute is intended to help prepare the large number of faculty required by engineering colleges in India and in the U.S. to meet the needs of industry in a global economy. Also contemplated is an Indo-U.S. Engineering Student Network to facilitate student internships and interactions and provide access to high-quality learning materials. It will be linked to the Global Student Forum currently sponsored by ASEE and the International Federation of Engineering Education Societies (IFEES), an umbrella organization of engineering societies, deans councils and student groups. These efforts are expected to benefit India by increasing the number of qualified engineering faculty, including more Ph.D.s; offering students access to better curricula; producing graduates with skills needed by industry and encouraging research. Benefits to the U.S. include opportunities for global experiences for faculty and students, collaborative research, development and entrepreneurship in emerging technologies of global relevance, and access for U.S. universities and companies to well-trained engineering graduates from India. Infosys, the Deshpande Foundation, and the Indo-U.S. Science and Technology Forum provided initial planning support for the forums. Additional corporate support came from Agilent Technologies, Autodesk, Dassault Systemes, Hewlett Packard, The Mathworks, Microsoft, National Instruments and Siemens. The U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, IFEES and the Indian Society for Technical Education (ISTE) were also important partners. Spencer Potter is ASEE’s International Programs Associate. |

India’s paucity of training resources is so acute that leading employers like Wipro, Infosys and HCL have been compelled to invest heavily in assisting universities and training institutes, going well beyond the standard internships and campus recruiting seminars. “It will take a while for universities themselves to scale up,” says Wipro’s Pratik Kumar. “Until that time, organizations will invest in helping them.” Corporations routinely send their own staff to guest-teach and help professors stay current by offering them training in fast-moving fields such as Java and embedded systems. New hires can expect to keep studying throughout their careers at Wipro, where starting this year all 65,000 employees will have access to 2,000 E-learning courses covering technical subjects and business skills, as well as domain areas such as insurance and retail. The company has 129 in-house full-time faculty—a university within its own walls.

Like its competitors, Wipro is also looking beyond engineering majors. “If the engineering population is just 7 or 8 percent of all grads, and Bachelors of Arts and Commerce is 64 percent, can we afford to overlook that pie? We can’t,” declares Kumar, who is executive vice president for human resources. About a fifth of Wipro’s intake is science graduates who get up to speed by taking IT courses on the job. Kumar says only a few thousand Wiproites are non-Indian now, but that in the future, to hedge risk as the company moves into higher-value-added areas of the still-nascent business process sector, Wipro is looking to aggressively hire not just in eastern Europe but also in Canada and Latin America.

Similar sentiments were expressed by two entrepreneurs, former Stanford mechanical engineer and Indian Institute of Science professor Krishnan Ramaswami, who is now chief technology officer for 3D Solid Compression Ltd., and K.K. Venkatraman, the startup’s CEO and an ex-Wiproite. “If people exhibit the right kind of skills, we should be able to train them,” declares Venkatraman. The startup recently took on a former welder who, as it turned out, had a talent for designing 3-D models.

3D Solid Compression is one of a handful of startups produced by the elite IIS, which also aspires to play the role of incubator, à la Stanford. “Unlike 10 years ago, the atmosphere is entirely conducive to starting a company,” says Venkatraman. “A lot of people want to break out of the mold. People are more willing to take risks now.”

On the outskirts of Bangalore, a former bank building is now occupied by another IIS professor, Dr. K.V.S. Hari, and his startup, Esqube Communication Solutions, which specializes in signal processing technology. “In the past, when we started companies, we had to use our spouses’ names,” he says, recalling the frustrating roadblocks of the previous highly regulated era. But as of 2000, reforms allow faculty to hold equity in their firms. At last, he says, professors have the liberty and venture funding to start converting their cutting-edge research into products.

“We’re now at a stage in tech education where the U.S. was 40 years ago,” iiit-b’s Sadagopan comments. “But the bet is high we’ll have a Silicon Valley in 15 or 20 years.”

While some Indians still grumble about slow reforms, the feverish pace of change evident here makes Bangalore feel less like a slow-moving elephant and more like a pachyderm stampede.

Lucille Craft is a Tokyo-based freelance writer who files regularly for CBS News and PBS’s The Nightly Business Report.

Category: Cover Story