Those Who Can, Teach

BY MARY LORD

Campus centers whet instructors’ appetite for a fresh approach.

Think back to your undergraduate days and what drew you to engineering. It probably wasn’t those long lectures in huge introductory courses or the fleeting contact with star professors. Now consider your own students. Do they doze, text, fidget, or routinely fail to finish exams?

Robert Butera, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology, knows how to combat such signs of disengagement, thanks to the Center for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning. He learned to punctuate classes with pop quizzes and group activities, keeping minds alert while providing quick progress checks. And he now limits lecturing to five-minute bursts, so material sticks. “The way we were taught as undergraduates, and the way most faculty still teach, is to prepare notes and lecture to students. And that’s not the way students learn,” observes Butera, whose yearlong stint as a CETL teaching fellow helped him co-develop Georgia Tech’s first freshman-level electrical and computer engineering course.

Part individual coaching, part classroom tips, part pedagogy workshop, and part resource for individuals conducting their own instructional scholarship, teaching and learning centers began as outposts at a few education schools about two decades ago. Today, their education specialists – typically, researchers steeped in the learning sciences – offer guidance at more than 1,000 campuses across the country on topics from designing meaningful problem sets to how the brain learns. By concentrating on how students master material, these centers help faculty deliver content more effectively.

Along with their campuswide mission to prepare future faculty, some teaching and learning centers tailor offerings for engineers. Georgia Tech’s CETL and Carnegie Mellon’s Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence serve faculties heavy in engineering, science, and math. A few, notably at the Universities of Wisconsin and Washington, focus exclusively on engineering education, while the University of Michigan’s college of engineering commands the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching North, its own branch office of the main campus center. It is headed by a former electrical engineering professor, Cynthia Finelli. All share a core concept: The better the teaching, the better the outcomes.

The movement to involve engineering with teaching and learning centers has gained momentum as the National Science Foundation and National Academy of Engineering have sought to improve curriculum and encourage more U.S. students – particularly women and other under-represented groups – to pursue the discipline. “There’s a whole lot we can do to help students understand what engineering is, understand what engineering thinking is, and get them jazzed about it,” says Sandra Courter, director of the Engineering Learning Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

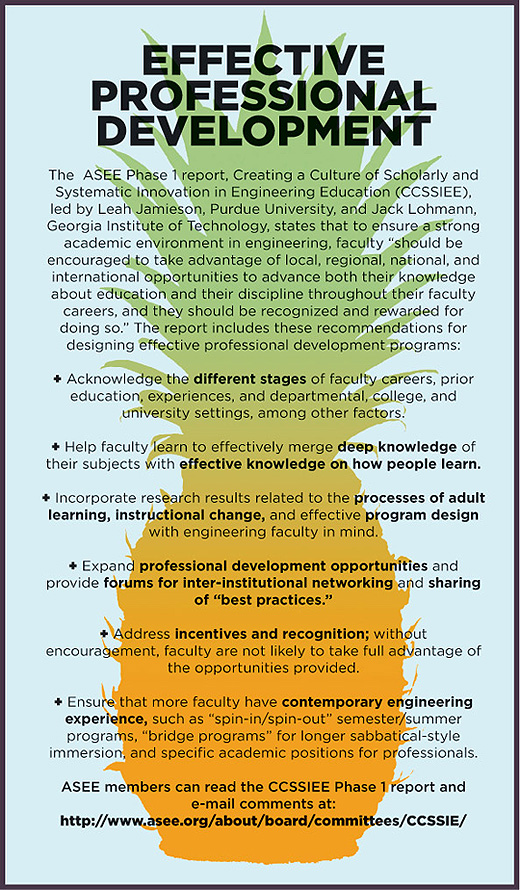

The next phase, argue Leah Jamieson, dean of Purdue’s college of engineering, and Jack Lohmann, an engineering professor and vice provost for faculty and academic development at Georgia Tech, is to “create a culture of support” for educational innovation – which means developing, recognizing, and rewarding talented practitioners. Jamieson and Lohmann presented highlights from their report, “Creating a Culture of Scholarly and Systematic Innovation in Engineering Education,” at ASEE’s 2009 annual conference. “While pedagogy cannot make up for lack of content,” the two authors assert, “inattention to pedagogy can seriously compromise learning.”

Avoiding a Stigma

Results from the brown-bag seminars, workshops, tech tips, and videotaped evaluations have shown such positive gains that many schools, including some departments at Georgia Tech and Michigan’s college of engineering, have mandatory orientation for teaching assistants. Other faculty may get a push from the department chair to participate in a center following an abysmal evaluation. Still, efforts are made to avoid attaching a stigma to the sessions. “We don’t hang out the sick-teacher-clinic shingle,” says Donna Llewellyn, director of Georgia Tech’s CETL since 1999.

As engineering educators become more effective, they often see student performance, course evaluations, and retention in engineering improve, as well. Some, like Butera, rediscover the joy of teaching. Indeed, one of the biggest bonuses for engineering educators is the sense of community that has developed around the science and practice of teaching, observes Finelli. Conversing with colleagues about teaching scholarship or classroom practice has changed shoptalk, she says. Now, when engineering faculty bump into each other, they are apt to discuss what’s going on in their classrooms, not just their research. “Teaching is becoming more public,” says Finelli. “It’s a culture shift.”

With the shift has come a growing sense of teaching’s importance. “If you’re on the engineering faculty, you do research and teach, and you want to do both as well as possible,” explains engineering professor Cynthia Atman, director of the Center for Engineering Learning and Teaching (CELT) at the University of Washington’s college of engineering. More than half the participants in Carnegie Mellon’s Eberly Center workshops are tenured faculty.

Offerings can vary from workshops on cognitive development to such tips as making eye contact with students. Teaching and learning centers also can intervene when a class veers off the learning track. Washington’s CELT has worked with 60 percent of the engineering faculty. The process varies little between disciplines, says assistant director and instructional consultant Jim Borgford-Parnell, who typically conducts intensive, one-on-one evaluations, in which he observes the class and jots down “ethnographic kinds of data,” including how engaged the students seem. He interviews students as a class and in small groups about what’s helping and hindering their learning, then distills their comments into a report with consensus items – aggregated data, “not just accolades and criticisms” – and suggested instructional changes.

Most instructors share what they learn from the report with their students, creating “a kind of rapport,” whether or not actual change results, says Borgford-Parnell. Simply soliciting student input can improve the classroom atmosphere, concurs Georgia Tech’s Llewellyn. Regardless of the results, reporting back “sends a powerful messagethat you care about the students. They come as partners to the learning experience.”

Videotaped evaluations also provide useful feedback. Llewellyn, who is right-handed, discovered she always looked to the right side of the classroom. From then on, she made a conscious effort to “vary the target” and face everybody. Her reasonably favorable reviews ticked up. Concludes Llewellyn: “There’s lots of right ways to teach.”

Michigan’s Finelli says she gains added credibility with engineering educators by having been one of them. “I was in the trenches for years,” says Finelli, who sprinkles seminars with examples from her circuits class and puts education buzzwords in plain terms. “The fact that I earned teaching awards makes a big difference.”

Old ways die hard, though, particularly given the constant struggle to balance teaching and research demands. “It’s very easy for me to take my lecture notes from last year, update them a little, and teach the course,” says Georgia Tech’s Butera, who has noticed that his course evaluations tend to rise or slide in inverse relationship with his neuroengineering lab and professional activities. “If I break up the lectures and introduce activities, that takes time, planning, and extra effort,” which can siphon off time from research.

Even if they accept the need to adopt new techniques, some faculty worry about shortchanging course content. Finelli tries to assure them that in just about every class there’s some wiggle room, prompting instructors to reassess what students must end up knowing. I ns teppingb ack,“ sometimes really important content turns out to be not as important as they thought,” says Finelli. “That frees up the class to do more activities.”

“There’s nothing like success to breed enthusiasm,” notes Llewellyn, and teaching and learning centers have ample evidence from professors that “Wow, that actually worked!” A survey of endowed Georgia Tech teaching fellows who had participated in CETL revealed stronger student evaluations, greater enthusiasm for teaching, and more innovation. Chemical engineering students were found to retain material better when group activities replaced the straight lecture format.

Budget Cuts & Flu

Innovation often proves labor intensive, however, making it hard to replicate. Butera’s freshman-level electrical engineering course using Lego robotics has two sections, each with one professor for 24 students – a fraction of the several hundred freshmen in the discipline. Departmental silos, tenure rules, and lack of institutional support also can stymie efforts to change the classroom status quo. So can budget cuts, requiring teaching and learning initiatives to adapt. Georgia Tech’s CETL, which took a 7.7 percent hit, has halted its newsletter for now and launched seminars on teaching large classes. Washington’s CELT is concentrating its efforts on junior faculty with workshops co-facilitated by engineering educators. Yet new pressures on universities can themselves spur useful teaching innovation. Wisconsin-Madison’s Engineering Learning Center is working with the engineering library on using technology to teach during pandemics, and it plans to relocate at the library to create a “one-stop shop” for teaching, learning, and research next year.

The development of teaching and learning centers coincides with a trend toward reframing engineering around multidisciplinary problems like the environment. A Wisconsin introductory course, for instance, connects engineering and such challenges as pollution and social issues. Georgia Tech is placing engineering faculty and labs next to molecular biology and environmental science. It may not be coincidental that some of the schools at the forefront of this trend are also ones that have placed a premium on better teaching. As for Butera, he recently concluded a yearlong stint as a Jefferson fellow at the U.S. Department of State. Look for his experiences there to add spice to his classes.

Mary Lord is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C..

Category: Features