When Disaster Strikes

BY MARY LORD

PHOTOGRAPHS BY LEE CELANO

Recovering from Katrina’s damage, two New Orleans engineering schools make emergency preparation a priority.

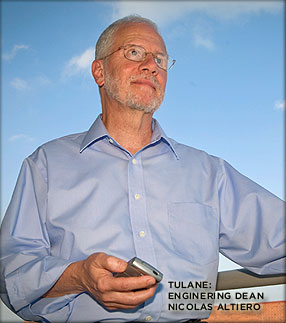

For Nicholas Altiero, dean of Tulane University’s College of Science and Engineering, August 29 was déjà vu all over again. Students had just settled into dorms and classes. Labor Day weekend loomed. And another monster hurricane was hurtling toward New Orleans, exactly three years after Katrina ravaged it.

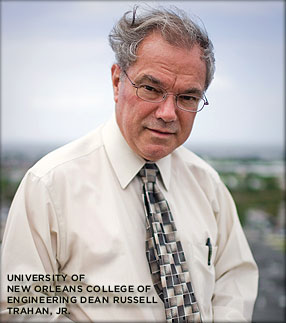

Across town on that same sunny Friday afternoon, the University of New Orleans closed campus and initiated its disaster plan as Hurricane Gustav advanced in the Gulf of Mexico. Mandatory evacuation seemed imminent. “Here we go again…” e-mailed College of Engineering Dean Russell Trahan, Jr.

Puny compared with Katrina, Gustav caused mercifully minimal damage, limited to downed tree limbs and damaged roof tiles. But it offered New Orleans universities a chance to apply dozens of lessons learned the hard way during Katrina and to activate sweeping emergency responses — from generators and evacuation buses to a resuscitated ham-radio operation — developed with the help of engineering educators.

“All emergency plans were executed nearly perfectly, as far as I can tell,” reported Tulane’s Altiero, who evacuated his own home that Sunday at 2 a.m. with his wife, cat and notebook computer, driving to a pet-friendly hotel in Jackson, Tenn.

Complex new preparations for life-threatening storms and floods represent just one element of Tulane’s and UNO’s prolonged, difficult and costly recovery from Katrina.

The Category 3 storm submerged two thirds of Tulane, causing overall losses to the university of $650 million, including $200 million in property damage. “Most of New Orleans had this bathtub ring,” recalls Altiero, who had spent the early days after Katrina making sure all his faculty, staff and students had survived.

A four-month blitz of scrubbing and repairs, funded with a line of credit, restored Tulane’s appearance, but a $100 million Tulane Relief Fund was insufficient to keep programs intact. Schools were reorganized and hundreds of jobs cut. To make better use of available money, the college of engineering was integrated with the college of science. Tulane no longer offers civil, electrical or mechanical engineering. Instead, those disciplines now reside in an engineering physics program that was created in partnership with the physics department.

Altiero, who became dean of the newly combined school, insists engineering remains as robust as ever at Tulane. “Biomedical engineering is alive and well” along with cell and molecular biology, he says. Other engineering disciplines were merged with appropriate science departments.

At UNO, which overlooks Lake Pontchartrain, Katrina’s most disturbing legacy is a shrunken student population. Enrollment “took an unbelievable hit” and has been slow to rebound, says Trahan. After serving as temporary lodging for 1,000 hurricane evacuees who survived without electricity or easy access to food, the campus didn’t reopen until the following spring. Despite efforts to draw students to online courses and off-site classrooms, many didn’t return. Today enrollment hovers around 12,000, down from a pre-Katrina level of 17,300. The resulting cut in tuition income has forced UNO to lay off or furlough some faculty and staff, though the school has tried to do so through attrition.

Physical damage topped $100 million. Equipment losses alone ran into the millions. At the nine-story engineering building, the only academic facility that flooded, the first floor filled with 18 inches of water, ruining all the equipment kept there. The water damaged most of UNO’s civil engineering labs and several mechanical engineering labs. Wind broke windows and damaged vents on the roof.

With FEMA and the state of Louisiana both involved in tallying damage and freeing up public money, repairs have been slow. Contractors showed up only this past August to fix the first floor, and repairs and replacement of damaged equipment were expected to take months. “The wheels of bureaucracy turn very, very slowly,” observes Trahan, who has relied on private-industry test labs and other “almost magical” substitutes to give every student a lab experience.

With such losses, not to mention the death and injury that occurred elsewhere in New Orleans, it was a given that both universities would work to limit the damage and disruption of the next storm. Engineering educators have helped strengthen infrastructure, refine forecasting and improve communications. Tulane biomedical engineering professor Cedric Walker even resuscitated the school’s amateur ham-radio operation, with its vintage W5YU call letters, and hooked into a digital ham-radio network that can transmit simple e-mail.

Here are important lessons learned, some of which may benefit others schools in catastrophic situations:

For Evacuee, Long Talks and Nintendo 64

Sophomore Emmanuel Michaelides, a neuroscience major in the College of Science and Engineering at Tulane University, had barely cracked his fall-semester textbooks when Hurricane Gustav forced the school to close.

As a New Orleans native, Michaelides, 20, knows the hurricane drill better than most undergraduates, having fled Katrina three years ago with his family. This time, however, he decided to board an evacuation bus bound for Mississippi’s Jackson State University, where a gym was being readied as an emergency shelter for 1,000 people.

“I kind of wanted to be an evacuee,” he says.

Michaelides quickly gathered his emergency kit: driver’s license, voter registration card, cellphone, Isaac Asimov novels, biochemistry text, bandages, Tylenol, bedding, and enough clean clothes for at least five days. “You need to take everything as though you were not coming back for a while,” he notes.

Once they arrived, boredom soon proved the biggest problem for the 181 engineering students destined to spend a week sleeping on the gym floor. But after a couple of days, tedium sparked creativity, including shopping trips for TVs and computer games, salsa and swing-dance classes, remote-control car races, Monopoly marathons and Nerf gun wars. Students practiced elementary Spanish with native speakers and developed a Zombie Evacuation Plan in case aliens ever invade a large city. Michaelides busied himself with science fiction, biochemistry, and vintage Nintendo 64 computer games. Tulane students who used the weight room and student center got better acquainted with their hosts.

Tulane students had access to Jackson State’s library, cafeteria and recreational and e-mail facilities. All the same, they gained some sense of the uneasy displacement of evacuees. Even if the electricity were off in New Orleans, “We’d rather have our beds back and be in our own classrooms,” says Michaelides.

Still, the “hurrication” provided a rare opportunity for long conversations with fellow students. Michaelides found that he “learned new things about old friends.” It was, he concluded, “a lot of fun.” And he’d do it again. —ML

1 Learn 2 Txt Msg

Katrina hurled communications into the void. The entire 504 Area Code went down. So did university Web sites, computer servers and e-mail systems, preventing administrators from posting information or contacting far-flung faculty and students. Circuits remained jammed for weeks. Altiero’s BlackBerry — which had a New Orleans number — couldn’t receive or initiate calls or e-mail. That’s when he discovered text messaging. “Suddenly, this message pops up: ‘Are you guys OK?’” recalls the Tulane dean. UNO’s Chancellor Tim Ryan received a similar crash course. For over a week, universities were running on text messages.

2 Get Multiple Non-local Contacts

At both Tulane and UNO, students now are asked to supply the university with their cell and home phone numbers, and non-university e-mail address. Everyone is encouraged to sign-up for text-message alerts, a fixture since last year’s slayings at Virginia Tech.

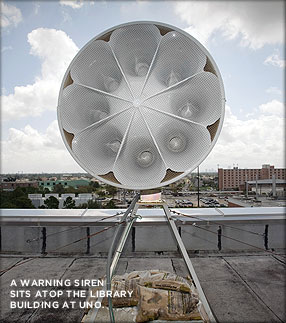

Both universities now have cellphone numbers and alternate e-mail addresses for every engineering faculty member. Altiero also has a non-504 phone number for every staff member. David Richardson, director of UNO’s Environmental Health and Safety Office, recommends having “at least one old phone that doesn’t need electricity” (i.e., not cordless) for when power is out and cellphone networks are down. Meanwhile, UNO is adding a second warning siren.

3 Mirror Web sites and critical data off-campus

Drowned Web sites were another unanticipated Katrina complication, prompting both Tulane and UNO to invest in backup “mirror sites” on distant servers. These will allow faculty to function no matter where they’ve evacuated.

After Katrina, Louisiana State University hosted a bare bones emergency Web site for UNO, so that’s where UNO’s mirror site now sits, with a second backup in Shreveport. Tulane has set up a site in Philadelphia.

4 Post Emergency Plans and Up-dates on the Web

During hurricane season, UNO’s home page features a link to its emergency plans. If disaster strikes, the university’s public relations department will take over sections of the Web site to broadcast alerts, bypassing the school’s computer system.

During Gustav, both UNO’s and Tulane’s home pages featured weather bulletins, toll-free emergency alert lines and updates on everything from when classes might resume to photos from campus. Tulane President Scott Cowen posted a daily “Scott Report” and fielded questions from students and families in live online chats. So as not to be dependent on the media to track potentially disastrous hurricanes, Tulane has enlisted a private forecaster to supply e-mail updates.

5 Prepare for Evacuation

In addition to university-wide emergency plans, each Tulane department and research center has specific, detailed procedures not only for evacuation but also for before and after the storm to secure engineering lab assets.

Students at both Tulane and UNO are urged to develop personal evacuation plans specifying where they will go, how they will get there and the names and contacts of any travel companions. New-student orientation at Tulane now includes a “hurricane talk” from the director of the Office of Emergency Response. It details such evacuation-kit essentials as a driver’s license, passport, ATM card, flashlight and laptop.

UNO purchased two buses solely to evacuate students to an off-site emergency shelter at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, after planners realized any leased vehicles would be commandeered by the state. Tulane, which contracts with out-of-state bus services, arranged emergency shelter at Jackson State University.

6 Create Off-site Central Command Posts

When Katrina scattered staff and decimated administration, UNO’s chancellor and deans regrouped in a conference room at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Sharing these cramped quarters, they could receive the same information and communicate well. Now, UNO has established a permanent emergency command post in Baton Rouge, where Trahan and other leaders will convene in any extended evacuation.

Tulane’s senior administrators will head to Nashville, Tenn. or Houston, Texas.

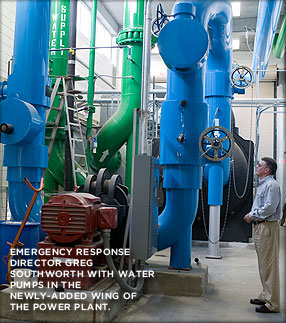

7 Establish an On-Campus Emergency Power Source

To protect computer systems and other assets, both Tulane and UNO have invested heavily in generators as well as huge fuel tanks to run them and a fleet of service vehicles.

Tulane built a command post hardened against hurricanes atop its generator. From there, a trained emergency crew kept an eye on Tulane’s three campuses during Gustav.

8 Make Emergency Preparation Routine

Engineering schools, particularly in bio- and chemical engineering, have microscopes and other expensive equipment that need to be kept cool. Research projects, cell cultures and creatures need tending. Tulane, for instance, has two vivariums. During Katrina, facilities managers could get to campus and feed lab animals, but there was no place to purchase the liquid nitrogen needed to cool the equipment. So now, Tulane stashes reserves around campus.

Pre-Katrina, UNO ordered an extra 500 gallons of diesel if a storm appeared headed for the Gulf. Now, every Thursday, a supply of diesel is ordered, and departments are urged to fill their vehicles.

9 Surprises Occur, Despite the Best Plans

Even with hardened command centers, text-message alerts, emergency power and at least one screen in every office tuned to the weather, disasters always bring surprises — and new lessons.

Ironically, UNO’s emergency plans may have suffered the worst hit from Hurricane Gustav. Both its mirror Web site and emergency administration headquarters are housed in Baton Rouge — which bore the storm’s brunt and remained without power for weeks

Web Links Vital in Galveston

When in 2005 Texas A&M took in numbers of Katrina-scattered students, it also absorbed sober lessons on weathering disasters. Results of that crash course were on prominent display this September. Days before Hurricane Ike clobbered Galveston’s flagship marine-systems engineering school, Web and E-mail alerts ordered students to evacuate. Damage reports and recovery plans got posted daily, along with reminders to update emergency contacts. Meanwhile, computer and e-mail servers were moved 125 miles inland to the College Station main campus, allowing students and faculty to keep up at least sporadic communications.

Ike left Galveston Island looking as though a giant weed-whacker had buzzed through, splintering residences and businesses and rendering uninhabitable the homes of faculty, staff and students. A week after the hurricane, the sweltering city still lacked water, power and sewer service. The causeway to Pelican Island was buckled and broken. Moreover, flooded lines ensured that the island’s entire wiring would have to be replaced. Though structural damage to university buildings was minimal, the beachfront campus and maritime academy were still ravaged. Gerard Coleman, senior lecturer in marine engineering and coach of the sailing team, doubts his sailors will return to the water any time soon, as their boats are “scattered all over the place.”

Texas A&M opted to keep students, faculty and staff at College Station for the rest of the fall term. Again, the Web site proved a key administrative tool. Polls asked who could relocate and when they could teach or take classes, and whether distance education was an option. Online sign-up sheets facilitated registration, with faculty teaching evenings and weekends to accommodate the space crunch.

The influx of more than 1,200 students has taxed the main campus, already struggling to accommodate a record 42,126 students. Parking for a football game was at a premium, because evacuees had taken over the lots. Still, within a week of Ike’s landfall, Galveston’s engineering program was back up and running — albeit remotely. As one Galveston engineering evacuee exhorted his fellow Aggies in an e-mail: “GIG ‘Em and we’ll get through this!” —ML

Mary Lord is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C. She co-authored the prizewinning “Down But Not Out,” about Katrina’s aftermath, in the Nov. 2005 Prism.

Category: Features

When in 2005 Texas A&M took in numbers of Katrina-scattered students, it also absorbed sober lessons on weathering disasters. Results of that crash course were on prominent display this September. Days before Hurricane Ike clobbered Galveston’s flagship marine-systems engineering school, Web and E-mail alerts ordered students to evacuate. Damage reports and recovery plans got posted daily, along with reminders to update emergency contacts. Meanwhile, computer and e-mail servers were moved 125 miles inland to the College Station main campus, allowing students and faculty to keep up at least sporadic communications.

When in 2005 Texas A&M took in numbers of Katrina-scattered students, it also absorbed sober lessons on weathering disasters. Results of that crash course were on prominent display this September. Days before Hurricane Ike clobbered Galveston’s flagship marine-systems engineering school, Web and E-mail alerts ordered students to evacuate. Damage reports and recovery plans got posted daily, along with reminders to update emergency contacts. Meanwhile, computer and e-mail servers were moved 125 miles inland to the College Station main campus, allowing students and faculty to keep up at least sporadic communications.