Down, But Not Out

By Thomas K. Grose, Mary Lord and Lynne Shallcross

Photographs Courtesy of Jeremy Martin.

IT’S BEEN ANYTHING BUT EASY. After Hurricane Katrina pummeled New Orleans in late August, Tulane University and the University of New Orleans (UNO) both had to shut their doors for the fall semester.

Tulane’s engineering college has managed to place its students at other universities, while UNO is offering dozens of engineering classes online in subjects ranging from robotics to hydraulics and wastewater-treatment systems- a useful course given the city’s vulnerability to flooding. Both schools vow to reopen their campuses by next semester, but that may be an uphill battle considering that New Orleans itself is struggling to survive. Gulf Coast schools beyond the Crescent City fared better, although some suffered serious damage. All told, the hurricane displaced an estimated 100,000 students and caused significant damage to 15 Gulf Coast institutions. Schools all over the nation reached out and offered homes to students and faculty members alike.

The federal government also came to the aid of displaced students. Congress approved legislation allowing affected students to keep all of the federal grant aid they received for college this fall. That legislation allows the secretary of education to waive a requirement forcing students who withdrew from college to return a portion of their Pell Grants. A number of federal agencies and organizations have announced policies with respect to the hurricane’s impact on faculty and research. The National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health have both said they will give scientists affected by the hurricane the time and money to get up and running again.

The American Council on Education asked its member institutions to help students remain affiliated with their home schools by admitting them only on a temporary basis. The council also recommended that schools not charge the students tuition if they had already paid at their institution and charge the home college rates to students who hadn’t yet paid, holding those funds in escrow.

In September, Hurricane Rita dealt another blow to the Gulf Coast area and a few of its universities. Among the hardest hit was McNeese State University in Lake Charles, La., home to almost 400 undergraduate engineering students and many displaced students from Hurricane Katrina. Most of the buildings and athletic facilities on the 98-acre campus were heavily damaged. Without power, water and phone service, the university was forced to close indefinitely. Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, was also clobbered by Rita, and about half of the 115 buildings on campus suffered extensive roof damage thanks to the 120-mph winds. Lamar, which has almost 950 undergraduate engineering students, was forced to shut its doors, but officials vowed to complete the fall semester. Both schools said they hoped to be up and running by late October.

TULANE UNIVERSITY

SITUATED IN THE HEART OF NEW ORLEANS, Tulane had no choice but to close for the fall semester. But President Scott S. Cowen vows its doors will reopen for the spring term. They must, he says, if Tulane is to continue as a major research institution. And, Nick Altiero, dean of Tulane’s School of Engineering, is confi dent that goal will be met.

But as university officials drafted strategies for Tulane’s resurrection, they had an even more pressing and logistical problem to attend to: finding temporary homes for the university’s students and faculty. For the engineering school, that meant seeking placements for about 700 undergraduate students and around 200 graduate students (40 percent of whom are foreign), as well as 60 full-time faculty and 25 staff members. Altiero estimates that about 80 percent of his undergraduates come from outside Louisiana.

Cowen arranged for Tulane students to enroll at other schools as “visiting students” for the fall term. “The vast majority of our students have taken advantage of this program,” Altiero says. “We are advising them via e-mail and Internet blogs.” By early September, Altiero categorized the undergraduate situation as under control. “It is more difficult placing graduate students and faculty.” Many faculty members who have found work elsewhere have taken their grad students with them. Hardest of all to place were graduate students who hadn’t yet been assigned faculty advisers, “especially students who had just arrived on campus the week before the storm.”

While there’s a worry that some students will decide to give up on Tulane, the dean says he is “confident that the vast majority will return in the spring.” Students have been telling him that they appreciate the school’s efforts to find them places at other schools for the fall as well as its plans for a flexible spring semester, ensuring that they won’t lose time toward their degrees.

As for relocated faculty members, Altiero says he thinks most appreciate the fact that Tulane continues to pay their salaries. “Of course I’m worried about losing good faculty members,” he says, course I’m worried about losing good faculty members,” he says, “but I am very optimistic that they’ll return home.”

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

ANTHONY LAMANNA

- Tulane assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering

- Half-time visiting professor at the University of Nebraska

I had a more difficult hurricane experience. My neighbor Randy had a housewarming party on Friday night after finally completing a total rebuild on his house the previous week. We all went to bed thinking Katrina was going to make landfall 100 miles east of us in Florida. I woke up at 10 AM to my neighbor Dave banging on the door and yelling “Katrina’s coming, Katrina’s coming.” Half asleep I was thinking, “Who’s Katrina? Do I need to shave and dress nice before answering the door?”

After shuttering our houses and helping many of the elderly in the neighborhood board up their at-risk windows, we spoke with many of the neighbors. It was clear that a lot of the old-timers were not going to leave, despite the worst predictions. It was then I decided to stay with Dave and take the elderly neighbors who would at least go to Tulane to the old, sturdy, 3 story building on campus to weather landfall. My Graduate student Huajie Liu and his wife Ying had also sought refuge in the building. We all weathered the storm there without any damage to the building we were in.

After the storm, Dave (A high school teacher at East Jefferson Public School) and I put on hard hats and road vests and cleared the road of downed branches while making our way home and discovered that both of our houses survived with very minimal damage, and that our cars were OK. We drove back to the University to pick up the neighbors.

About 3 hours after the storm passed, I took a walk around the block to Maple Street, the location of several restaurants, shops, and salons to see the damage. I was taking pictures of the damage to some new construction when I noticed four youths running from a store with armloads of dress clothes. I couldn’t believe there was looting so soon after the storm. It really got to me that this was occurring in my own neighborhood.

The following day I walked down St. Charles Avenue with my neighbor Rydell, a special education instructor, to check on my friend Billy who weathered out the storm in his house on St. Charles Avenue by Washington Avenue. We saw many people out, walking dogs, jogging, and walking to dryer areas from the 9th ward (a very low-lying neighborhood, you have seen it on the news). As we neared the intersection of Louisiana Avenue, we observed people looting the gas stations and mini-marts in the area. We kept walking to Billy’s house.

Billy was just fine. We chatted for awhile, and decided to drive back uptown to my house so that Billy could take my generator back to his house. Rydell had a generator that could keep a refrigerator and an AC going in the neighborhood, so I didn’t need mine. We drove up St. Charles, criss-crossing the neutral ground to avoid downed wires and tree limbs. All of the live oaks were still standing, and only a few crepe myrtles were downed. Uptown had fared quite well through the hurricane.

My neighbor Randy accompanied me back to Billy’s with the generator; he walked back up St. Charles with me after a few cold drinks at Billy’s. Again, around Louisiana Avenue there were many people looting, and this time, several of them started approaching us, without speaking to us. We sped up, and to be safe, I took my revolver out of my pocket and held it openly in my hand. Then people backed away and left us alone. We decided to stop making trips to Billy’s.

The next day, Randy and I were walking around the neighborhood and we observed some flooding that wasn’t there before. We had heard on the radio of the levee breach at the 17th street levee, but that was a long way from our part of town. We walked a bit further, and on Broadway Avenue encountered three men with rifles slung over their shoulders. We stopped to chat; they informed us that they were on their way to one of their father’s house to pick up some more guns, and then they asked us if we needed more guns. We responded we were ok, and headed back to our block. As we got to the end of our street, Randy and I stopped dead in our tracks. We saw the water moving in the street, and both stood still thinking we were creating wakes. We weren’t. The water was rising on the street like the tide. Between the guns and the water everywhere, it was time to go.

As we got on the block, two cars had already left. Dave was packing up the last of the elderly neighbors and was almost ready to leave. I didn’t want him to leave without a gun, so Randy and I hurriedly packed in 10 minutes to accompany them out of the city. I remember in my house, I stood there and asked myself, “What do I absolutely need?” I packed my two cats, a small suitcase of clothes, and took my box of important papers. Randy packed his things into my jeep. We took a saw with us, in case we had to cut through some branches on the way. We also packed batteries, food, and water in case we didn’t make it out of the city and couldn’t get back home.

We drove down St. Charles for awhile, and it was eerie looking through Audubon Park all the way to the zoo. The hurricane had stripped most of the trees of their leaves. As we turned down to go to Tchoupitoulas, we slowed down and spoke to a man in a car traveling in the other direction. Another NOLA native trying to leave the city, taking another route. We exchanged information on the routes we came from, and I offered him a cold drink from our cooler. We had packed the last of our ice with some drinks before we left.

As we drove down Tchoupitoulas, we saw several police cars circled around the Winn-Dixie parking lot. They were coming out of the store with bags of groceries. Further down, we saw people on foot trying to drag a driver out of his car; he smartly sped up. We followed suit, and I made sure my gun was prominently displayed for the people on foot to see. We drove past the Wal-mart that had been looted; there was trash all around on the streets. We made our way onto the Crecent City Connection. The scene was surreal. People were walking across the bridge on foot, with trash bags full of their belongings slung over their shoulders. In the distance behind us, the superdome waterproofing membrane was missing, but the structure still seemed ok.

We took the Westbank Expressway to the 310, the 310 to I-10, then went west. Right before the I-55 split, I blew a tire. We were going about 90 mph, but I managed to pull over to the side of the elevated highway. Dave continued onto I-55 north to loop around to Atlanta. Randy and I were headed north to Shreveport. That’s where I had evacuated for Ivan last year, and knew I had a place to stay for at least a night there. I had lost my cell phone before the hurricane, so I had no contact numbers. Randy stood in the road to keep people away from me while I changed the tire.

We continued to Baton Rouge, and ended up stopping at Gordon and Sandifer Auto Service to get a new tire. I had thought that we might be price-gouged, but the tire was about $40 less than I paid a month prior in New Orleans for a new tire. The gentleman was kind, and his wife even made some fresh coffee for us. He was upset that he only had a white-wall that didn’t match my other tires.

We continued on to Shreveport. We were shocked when we were traveling quite fast and were passed by about 15 to 20 New Orleans Police Department cars with Winn-Dixie bags in the back windows. We can’t say for sure they were the same cars that we saw in the parking lot back in New Orleans, but it wasn’t a good sign they were leaving the city. A few minutes later, we saw a caravan of fire trucks, police cars, and ambulances with “LA” painted on the sides on the opposite side of the highway headed to New Orleans. I said “Where in LA?” but then realized they had come from Los Angeles. Amazing. These people had driven from California to help.

We got into Shreveport at dusk. I knew that my friend Melissa, whom was my neighbor my first year living in New Orleans, was back living in Shreveport, and her father owns one of the top restaurants in town. I stopped at a gas station, and the first person I asked about Fertitta’s gave me directions. When Randy and I walked into the lobby, we were warmly welcomed with open arms by Melissas mother. We spent the night in Shreveport, left the cats with Melissa, and continued north. Our reasons for going north were: 1. I had a friend in Omaha where I knew I could stay for a few weeks to get back on my feet, and Randy would be welcome too, 2. we wanted to get far away from New Orleans, 3. I had friends every 5 hours or so along the way, 4. we wanted to stay ahead of the advancing wave of misplaced hurricane survivors, and 5. we wanted to stay in the same time zone so I didn’t have to figure out how to change the clock in my jeep. (OK, #5 is a joke).

We left the next morning for Hot Springs, Arkansas. I had a friend there I knew from college, who works at the school for gifted kids. When we stopped at the rest area in Arkansas, we asked the information desk lady about the school. Amazingly her daughter attended the school, and she gave us detailed directions how to get there. We arrived at the school later that day, and asked for my friend Alaine, the librarian, at the front desk. She came down and was happy to see us.

Alaine helped me locate a similar cell phone to the one I had previously, in Little Rock. The company said that if I bought a similar phone, it would down-load all of my contacts. After much hassle in the Comp-USA and several calls to the cell phone help-line, I was up and running.

We spent the next night in Fayetteville, AR with my friend Micah, an Assistant Professor at U of Arkansas. We met while he was finishing his Ph.D. at U of Oklahoma when I was interviewing there. We both were interviewing for all of the same jobs at the time. We have since become friends and hang out at conferences together and swap stories about our jobs.

The following day Randy and I rolled into Omaha, during the 3 day weekend. I could feel my body relax when we were 20 minutes from Omaha. Our adrenaline-drive was near an end. I was suffering from cramps from not being able to keep any food down since we had left New Orleans. We arrived at my friend Lisa’s house, and went out to a Steakhouse for dinner. It was a wonderful dinner, and it stayed down. The next day, I had not heard from Tulane University, and didn’t even know if I had a job.

I started asking Lisa and her friends about potential employment in the public high schools as a substitute teacher, in engineering firms (I had just earned my PE 2 months earlier in July), or about colleges in the area. Many locals were telling me about the new Peter Kewit School of Engineering and Technology that was new and growing. I was familiar with Kewit, and thought that my Ph.D. professors at the University of Wisconsin – Madison might know somebody at the school and could put me in contact. I sent some emails and made some calls to Dr. Larry Bank, my Ph.D. advisor, and Dr. Jeffery Russell, the current chairman of the CEE department at UW. Tuesday morning they placed calls, and sent emails, and by 10 AM I was contacted by Dr. Maher Tadros of the School of Engineering and Technology at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

I also want to say that I had several wonderful offers from my colleagues at the University of Oklahoma, University of Wisconsin – Madison, and others around the country to provide me space to work during these hard times.

I met with Dr. Tadros and Dr. Jim Godert, Chair of the Construction Systems Department, for lunch that Tuesday. I still hadn’t heard from Tulane. I told them a little bit about myself, and they seemed interested in having me on board for the year. I was initially offered a visiting professorship for the year.

Later that night, I managed to get ahold of Nick Altiero, Dean of Engineering from Tulane University. He was on his way to Houston to meet with the administration where they had set up shop there. He had mentioned I could accept a half time Visiting Professorship, to ease the burden on Tulane for the semester.

So on September 15th, I signed a contract with the University of Nebraska to be a half-time Visiting Assistant Professor for the year, with an option to leave in December if called back to New Orleans by Tulane University.

Once I knew I would have space for myself at the UN, I contacted my graduate students and let them know they had a place to work here, and I would assist them in finding housing. I received word that Jeremy Martin, an MS. Student, and Huajie Liu (Leo) and his wife would be coming to Omaha. On Thursday the 8th I went online and saw a pop-up ad for hurricanehousing.org. I flipped through over the 100 listings of rooms and apartments available for misplaced hurricane survivors, and thought that the students could look themselves when they got here. One ad caught my eye. It was for 5 people, so I examined it closer. The woman had taken her house off the market for 6 months so that hurricane survivors could live there. I called and made an appointment for 6 PM on Friday.

The students rolled into town about 3 PM on Friday. They had spent the previous night with my friend Micah in Fayetteville, AR. We rested a bit, then I dragged them to see the house. Rather, I should say, so that Karen could meet us and feel comfortable with us staying in her house. The house was wonderful; a small bedroom, a large bedroom, full bath upstairs, living room, kitchen, and half bath on the ground floor, and a small bedroom, laundry room, and garage in the basement. The most interesting thing of all was bronze fleur-de-lis on the light fixtures in the hallways. Almost as if people from New Orleans were meant to be there.

The next day we moved some furniture in, and over the course of the weekend we had kitchen equipment, beds, a couch, chairs, and all the trappings necessary for some semblance of normalcy in the house. Karen’s friends and family had brought over everything we needed.

So here we are. A professor, an American MS student, and a Chinese student and his wife living in a house in Omaha, conducting research and writing papers at the University of Nebraska. None of us would have ever thought we would be here if you had asked us 3 weeks ago.

My other graduate students are getting settled in elsewhere. One is in California getting settled at UC-Davis, another is at University of Maryland – College Park, and another at ‘Bama. Soon these three will be working with me again on their research projects via long distance.

The hardest part of this, for me, has been talks with my friends from New Orleans who have lost everything. I feel lucky that the academic community has pulled together to help faculty and students that have been misplaced from the disasters that have occurred in the Gulf Coast. I am thankful my house wasn’t flooded and that I have something to go back to, as well as a job at Tulane to go back to.

The relocation effort was boosted by the “overwhelming” response Tulane got from other universities. “Quite frankly, we are having a difficult time processing all of the offers of support,” Altiero said in mid-September. He received more than 300 e-mails offering assistance. Schools not only agreed to take in students, offering assistance. Schools not only agreed to take in students, but they also offered office and lab space, equipment and even housing for faculty and graduate students. “I can never thank the university community enough for how they came to our aid.”

Geography should abet Tulane’s efforts to resume classes in the spring. It’s located in southwest New Orleans, an area that experienced less flooding than some other areas. Only a handful of campus buildings were flooded, none of them used by the engineering school. Most of the damage consisted of broken windows. Given its location and lack of severe damage, Altiero says, it’s likely the area around Tulane will be the first area to get back on its feet. More worrisome-and still a big unknown-is how much the closure affected ongoing research programs. Some equipment and experiments requiring temperature-controlled environments could be harmed by the lack of power. “I’m worried about this,” Altiero admits. Several engineering faculty members have gone back in under university convoy to service critical equipment and retrieve important servers. They’ve been able to save experiments involving biological materials.

Still, many faculty members, staff and students might be returning to homes or apartments either destroyed or badly damaged. So Tulane’s spring plans include temporary housing for those with no homes to return to. And it is also working to ensure that there is K-12 education for the children of faculty, staff and students. Of course, some things are out of the school’s control: power generation and sewage, for instance.

Nevertheless, Altiero refuses to consider the possibility of failure. Jazz-inflected funeral marches figure prominently in New Orleans’ diverse musical heritage. But don’t count on striking one up for Tulane just yet. “The university,” Altiero insists, “will reopen.”

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

JEREMY MARTIN

- Tulane graduate student, civil engineering

- Enrolled at the University of Nebraska for the fall semester

First of all, let me begin by saying it is very strange to have received so much attention through the “flickr” photo sharing webpage. My original intent was to share the condition of my neighborhood with my neighbors and friends, so they would know that the worst case scenarios broadcast on TV were not true from their houses. I drastically underestimated the interest in the area. As I write this, the photos have been viewed almost 55,000 times, and I have received dozens of comments, notes of support, thanks, and requests for use from non-profit organizations and publications.

It is also very strange for me to be writing this in Omaha, Nebraska, really the last place in the world a guy from New Orleans would expect to find himself. Right now I am living in a donated house with my Professor (Dr. Anthony Lamanna), a PhD student (Huajie Liu – we call him Leo) and his wife, both from China. I am a 23 year old graduate student at Tulane University, and I am from New Orleans (though I have also lived in New York). I am currently in the process of getting my Masters in Civil Engineering. I received my BS from Tulane University (also in Civil Engineering) in 2004. I am doing my Masters research with my advisor, Dr. Lamanna, on the use of Fiber Reinforced Polymer strips to strengthen reinforced concrete beams.

My hurricane experience was, fortunately, rather uneventful. Prior to the storm, I had been backpacking with in the Sierra Nevadas. On the return drive we were without the news, and had no idea that the storm was headed to New Orleans. We arrived at a friends house Lafayette, LA late on Friday night, exhausted, and went directly to bed. When I woke up, Katrina had moved track almost directly over New Orleans, and we scrapped our plans to continue on into the city. We only got heavy wind in Lafayette. So I stayed in Lafayette for about a week, just waiting to see what Tulane was going to do. In the meantime, curiosity got the best of my friends and I, so we ventured into the city to check out our houses, and get a general sense of the conditions inside the city.

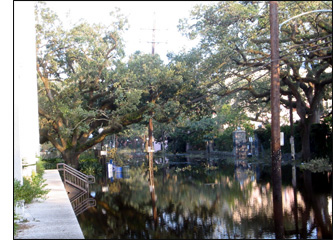

It was eerie in there. In order to get into the city, we had to navigate back roads, avoiding the few police roadblocks on the major roads. The air was dead still, and the floodwaters turned streets into mirror-surface canals, and the houses made these canals seem like they were at the bottom of canyons. Every sound we made echoed for blocks down the street, from hard surface to hard surface across town and back. As soon as I stopped waking to take a picture though, the echoes faded and the slice returned before it was disturbed by the “click” of the camera. The insides of houses were stuffy hot and humid. Mildew grew on the sheetrock and in the refrigerators full of decaying food. As I packed a bag with clothes (I only had a couple of changes with me before), a helicopter would occasionally rumble overhead. The experience of walking around, taking these pictures, was an adventure. I was like I was exploring my neighborhood for the first time, finding secret lakes, green piles of fallen branches forming gardens, apocalyptic upside down reflections of flooded cars and buildings which were rising out of the water. I watched the beginning colors of the sunset reflect off of my street, and we decided wit was time to go. On the way out we passed people with rifles, people who were eyeing our car, but we just sped on, up and over the bridge, looking back for a second and seeing blackness where there was once a city of light.

When we got back from the city, I volunteered in the Red Cross shelter in the Lafayette Cajun dome for a few more days (I honestly don’t remember how many), before receiving word from my professor that he had a place for me in Omaha. This put me in a strange place really, because I was enjoying my work at the shelter. I felt like I was in the middle of things, and that I was making a difference for the people who needed help the most. It took my mind off of my problems. Every day I was struck by the tranquility and bravery of the people in the shelter. People who had nothing were understanding, comforting me, encouraging me, and thanking me for my help. It was very difficult for me to leave, but a felt bad relying on other people for food and shelter when I had an alternative, provided by Dr. Lamanna.

We (Dr. Lamanna, Leo, Huiying and I) are currently living in a house that was taken off the market by its owner to house Katrina evacuees. She is providing the house to us free of rent, and even covering the utility bills until we can work out our monetary situation. Our house was furnished within 48 hours of my arrival, entirely by community members wanting to help us. I feel I cannot emphasize the kindness of the people in Omaha enough. It has been simply overwhelming. Their kindness has made the fact that I will be away from home until December somewhat bearable.

Tulane will remain closed for an entire semester. The nationwide academic community has been incredibly supportive, offering near-instant admission and often free room and board to Tulane students. Most (actually, all) of the responsibility for finding another school was placed on the students. Undergraduates, for the most part, seem to have found a place in school near their homes, or near the homes of friends. A large group of undergraduates from the Tulane Civil Engineering Department is now attending RPI, though most are not from the area. I think they realized it was a good idea to stick together in this trying time. Most of my Tulane friends are spread out across the country, from New Mexico to Florida to New York and points in between. I feel this is true for most students. I am still in the process of locating many people, because phones with 504 area codes are just now beginning to work again.

Graduate students have had a bit more difficulty, as we are concerned with more than simply coursework. My research will be my thesis, and I view that as my priority. Though Tulane was slow in releasing information and instructions for students in the first week after the storm, Dr, Lamanna got to work on his own with the administration here and has set us up very nicely (we do not pay tuition), with much help from the generous people at University of Nebraska. While we are here we plan on writing some grant proposals, but I will mainly concentrate on writing my thesis as well as academic papers on my research.

In the end, I miss home. I think about it every day. I grow angry sometimes at the negative news, and what I cant help but feel was an unacceptably slow response from the federal government. I swell with pride when I hear Ray Nagin’s (our Mayor) words of reason, when I hear him cry for help or demand action. I and proud that my city is managing to cope with this and will rebuild. This has been an experience I will never forget. In the past month I have crossed the country always in uncertainty. I do not know when I will be able to return to my city. The only reason I have been able to keep going has been the kindness of people at every step of my journey. The kindness of my friends in Lafayette, of the folks living in the shelter, of the online community, of my professor, of the people along my long drive north, and the kindness of the people in Omaha.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

Huajie Liu

- PhD candidate, Tulane University

- Temporarily at the University of Nebraska working with Anthony Lamanna

Leo and his wife Huiying also remained in New Orleans during the storm, and also sheltered in the old buildings on campus during the worst of the wind and rain. After the storm, when the water started rising, they moved their things into the second story of the house as his living room began to flood. Later they heard gunshots and became frightened. When a neighbor (who was armed) offered to take them out of the city, they jumped at the opportunity, and over the next several days went from New Orleans, LA to a friends house Clinton, MS to a church shelter in Baton Rouge, where they were kindly taken in later by a family at that church. Leo and Huiying stayed with this family until Jeremy Martin picked them up to go with him and Anthony Lamanna to Nebraska.

UNIVERSITY OF NEW ORLEANS

RUSSELL TRAHAN, DEAN OF THE COLLEGE of Engineering at UNO, expected a humdinger of a kick-off this academic year. His school was celebrating its 25th anniversary, and he had spent the sultry last days of summer preparing for a grand October gala.

Katrina doused those plans, along with computer networks and student records, turning the lakefront campus- or at least the two-thirds that remained above water-into what Trahan described as “an island with the surrounding homes flooded up to the rooftops.”

UNO has fared somewhat better than many parts of the Big Easy. For starters, few of the mostly commuter students got stranded on campus; those who didn’t leave in their own cars were transported to Louisiana State University (LSU) in nearby Baton Rouge and housed in dorms. UNO administrators, who had started assembling a team immediately after the hurricane hit, quickly established temporary headquarters at LSU. Three days later, a bare-bones version of the school’s Web site appeared with a phone-bank number and e-mail registry where students and employees could check in, as well as get answers to financial aid, paycheck and other frequently asked questions. Meanwhile, UNO’s student newspaper added a Katrina message board to the site. Among the first people sought: its scattered reporters.

It took almost two weeks before callers could get through the state’s jammed circuits. Dean Trahan-on duty since that first Wednesday- Trahan-on duty since that first Wednesday- was only then beginning to communicate regularly with his department chairs and had yet to locate all faculty and students. Of particular concern were new faculty members who had just moved to New Orleans. A damage assess- just moved to New Orleans. A damage assessment team finally got its first look at the campus Sept. 13.

The destruction proved less than originally feared. The first floor of the nine-story engineering building, which houses several laboratories, sustained about a foot of water. Two weeks before Katrina hit, the staff members talked about storing their ABET course assessment materials in the building’s basement. “Thank goodness we did not do this,” Trahan says. “All of our material is safely stored on the fifth floor.”

In mid-October, UNO began offering 800 online courses, 41 of them in engineering. “We will have a full semester this fall,” Trahan says. LSU’s College of Engineering, which has enrolled many evacuees as visiting students, “has been very, very helpful in advising and enrolling our majors,” Trahan says. He adds that the 30-hour residency require-jors,” Trahan says. He adds that the 30-hour residency requirement for graduation has been waived, allowing some seniors to earn a UNO degree in December.

More than the equipment, though, it’s the damage to the More than the equipment, though, it’s the damage to the work that worries officials. “Our researchers are having a particularly difficult time right now,” Trahan wrote in a mid-September e-mail, predicting “serious delays in some of our research efforts.” A few faculty members have been able to reconstitute their graduate teams at other universities, but many graduate students relocated far from Louisiana and lack the resources to continue their research.

Many UNO undergraduates appear to have weathered the uprooting in fine shape, due to the warm welcome extended by universities nationwide. Rayam Sader, a senior in mechanical engineering from Saudi Arabia, was amazed at how easily he enrolled at the University of Houston, which has absorbed more than 1,000 of his peers. The whole process took less than two hours-with no questions about tuition and an adviser to help match UNO requirements with Houston’s engineering courses, which had started a few weeks earlier.

UNO officials believe their campus will bounce back as strong as ever. Along with rebuilding their college, UNO’s engineering faculty promises to play a leading role in the region’s recovery. Trahan notes that his faculty has worked for years with the Army Corps of Engineers. “As part of the rebuilding of the city of New Orleans, I have a goal of making the UNO College of Engineering a contributor of ideas to ensure that we never experience this type of disaster again,” Trahan says. His own well-engineered home- built on a steel substructure “that performed exactly as it was designed”- got inundated by a 17-foot tidal surge. It left 4 inches of sludge in the above-ground basement, ruined the living area’s oak floors and carpets and rendered the place uninhabitable for months. “We are determined to rebuild our city, our lives and our university, the University of New Orleans,” vows Trahan, who is planning to hold a “bigger and better” 25th anniversary celebration this spring.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

NATALIE GUTHREY

- Tulane senior, biomedical engineering

- Enrolled in Boston University for the fall semester

My parents live about 100 miles west of New Orleans, so the evacuation part was pretty easy for me. Thankfully, our home wasn’t damaged. It was harder for students far from home who didn’t have any place to go. After the hurricane, we knew there wouldn’t be any school for the fall, so a lot of students started looking elsewhere. Tulane told us to find a school that was accredited and had comparable courses. Boston University was quick to respond and had my major, so I decided to go there. The faculty and staff have been incredibly helpful. All I had to do was show an ID and show that my Tulane tuition had already been paid. I don’t have to pay additional tuition to BU-I only have to pay for books and housing. When we first got here, BU did something really special to make Tulane students feel at home. They had a welcome dinner, and-this is unbelievable-the bookstore at BU contacted the bookstore at Tulane and managed to get hats and shirts for the visiting students. They had a Tulane hat and a shirt shipped in for each and every one of us, and they had them on the table when we walked into the dining hall.

Do I want to go back to Tulane? Yes, I really miss New Orleans. Most Tulane students consider New Orleans their home. There’s a Web blog of Tulane students, and they’re all saying the same thing. They want to go back. I’m looking at this as a really cool opportunity to be somewhere else for a little while but not to stay. My friends and I had been looking forward to our senior year. We loaded up on courses freshman through junior year so that we could take it a little easier for our last year. We enjoy being with each other and love New Orleans. It was really upsetting to find out that we will only get to spend half of the year together as we had planned. At the same time, we’re growing closer because of the situation.

BEYOND THE CITY

KATRINA’S WINDS HAD BARELY DIED DOWN when hundreds of colleges and universities across the nation began offering assistance to Tulane, UNO and other hard-hit schools. Their main focus was on helping students by offering admission for the fall semester. But how students would pay, show qualifications for admission and catch up on missed class time presented hurdles that are in some cases still being worked out. Schools from LSU to the University of Nebraska also extended a hand to displaced engineering faculty members.

Outside New Orleans, most engineering schools in the Gulf area and beyond survived the hurricane without significant damage. The University of South Alabama (USA) in Mobile, which lost part of the roof of its student recreation center to Katrina, closed for one week. The University of Alabama (UA) in Tuscaloosa, closed for a day after Katrina took down trees and briefly knocked out the power. While repairing whatever minor damage was done, these and other area schools wasted no time opening their doors to students-faculty and researchers were not forgotten either. A few hundred miles away, Purdue University’s College of Engineering, for example, offered visiting positions and housing for the fall semester to displaced faculty members, research staff and postdoctoral researchers.

For students, gaining admission became the first stumbling block as transcripts and official documentation were hard to obtain from their shut-down universities. Many schools relaxed the requirements, some even taking students on their word for qualifications. USA held two special registration sessions and temporarily waived the requirement for official transcripts.

Space became an issue at some schools, like LSU, where officials ran out of campus housing after more than 1,800 students from evacuated colleges registered for classes within days of the hurricane.

But finances presented an even bigger hurdle. Numerous schools have waived late fees and deferred tuition and housing payment deadlines until students from affected areas can assess their financial situations. Many, like UA, have also allowed some displaced students to pay in-state tuition rates or offered scholarships for the difference, as USA did. Other schools, like Boston University, have not charged students tuition if they had already paid to their home institutions. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute has waived the entire semester’s tuition, fees and room and board for students enrolling in its new Gulf Coast Visiting Scholars program. “I think everybody’s trying to just accommodate the students, get them into school, and we’re going to worry about the financial issues after we get them back in class,” says John Steadman, USA’s dean of engineering.

Once the requirements and finances were settled, or at least postponed for later, catching up in class proved problematic, says Jim Killian, director of communications and marketing at Auburn’s Samuel Ginn College of Engineering. When Hurricane Katrina hit, students at Auburn were already in their third week of class. Transferring immediately after the hurricane “means the student would have missed anywhere from six to 12 sessions of class, which if you’re an engineering student, it’s so tough to make up that class time,” Killian says. But that’s simply a note on how hard it is for engineering students to make up missed time, he says-not a policy that would prohibit displaced students from transferring to Auburn.

Universities in the Gulf area also worked to aid their own students and faculty members whose houses were directly impacted by the hurricane. UA’s dean of engineering, Charles Karr, says the university has been as flexible as possible with its students, recognizing that there are “more important” issues than education. “They’re going to struggle and for as long as it takes, we’re going to work with our students here,” he says. “We have no problem delaying the date they have to take a thermodynamics test if they have to go down there and help their family rebuild their home.”

If anyone could have foreseen this crisis, it was New Orleans’ engineering and science community. The faculties at the two schools include some of the country’s leading engineering experts, as well as environmental engineers whose research on the region’s wetlands and levees has spotlighted systemic weaknesses for years. Just last fall, UNO’s Shea Penland was quoted in a chillingly prescient National Geographic article outlining how a hurricane could destroy New Orleans. “It’s not if it will happen,” Penland said. “It’s when.” Now these same engineers hope to play a lead role in the city’s reconstruction- once they mop up their ravaged campuses.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

DAN CLARK

- Tulane freshman, environmental/civil engineering

- Enrolled in Boston University for the fall semester

I arrived to move in at Tulane early Sunday morning. By 10 a.m., they announced that we had to evacuate by 5. I had time to unpack my stuff, set up my room and get my ID card, a debit and checking account and a P.O. box. I didn’t even have time to grab my laptop, which is now stuck in the mail storage room at Tulane, hopefully undamaged. After only six hours of being a freshman at Tulane, my parents and I drove to Nashville, where they had planned to stay the week. When I learned Tulane was closed indefinitely, my parents and I continued our drive home to Connecticut and arrived Sept. 4. That night I began looking for universities accepting Tulane kids. It didn’t really hit me until I had to start looking at other schools that, wow, I’m not going back at Tulane this fall. I had to squeeze a year’s worth of the college selection process into Sunday night and Monday morning. Many universities were accepting Tulane students, but I went to BU, partly because it was close enough to drive to that day and also because they were taking Tulane kids for no cost. We drove to Boston that same day, on Monday, and I registered. BU took me solely on the basis that I was accepted at Tulane. I got an ID card, a meal plan, a bank account, engineering courses-all that day. And on Craigslist, I was amazed to find free housing from a woman whose son was also displaced from Tulane. I started my engineering courses the next day on schedule with the rest of BU. Needless to say, I was a little disoriented. But I was lucky. A lot of people weren’t, and every day I’m grateful. Depending on the clean-up in New Orleans, I definitely want to go back to Tulane. I loved it there when I was visiting and in the brief time before I had to evacuate.

Thomas K. Grose is a freelance writer based in Great Britain. Mary Lord hails from Washington, D.C., and Lynne Shallcross is associate editor at Prism.

Category: Features