Route to the Top

What do Fred Hassan, George W. Buckley, Michael R. Splinter, and David J. O’Reilly have in common? Well, they all breathe the rarefied air of some of America’s most important executive suites: Each is the chief executive officer of a Standard & Poor’s 500 company. Hassan runs Schering-Plough, Buckley 3M, Splinter Applied Materials, and O’Reilly Chevron. But there’s something more essential that connects this quartet of top execs. Each also has an undergraduate degree in engineering.

And that’s no rarity in corporate America.

According to Spencer Stuart, an executive search company that annually publishes a snapshot of America’s top CEOs, 21 percent of the S&P 500 companies—105 of them—are headed by executives with undergraduate degrees in engineering. That makes engineering by far the most common undergraduate degree among this select cohort of business people. CEOs with engineering degrees outnumber those with degrees in business administration or accounting by nearly 2 to 1 and 3 to 1, respectively.

“That’s a surprising statistic,” admits Thomas Allen, a Sloan School of Management professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and codirector of the Leaders for Manufacturing program. “But I’m delighted to hear it.” When he mentioned it to a few colleagues, applause nearly broke out. “We always felt our graduates were working for Harvard MBAs,” Allen joked. In the past, it seemed that no matter how qualified engineering graduates were for top jobs, they would be passed over in favor of business-school graduates. The 21 percent figure also surprised Harvey Palmer, engineering dean at the Rochester Institute of Technology–but for a very different reason: He thought there would be more of them. “It really should be higher,” Palmer says of the total number. Indeed, many engineering academics argue that engineering schools give their graduates skills and training that should bolster their chances if they want to scale the corporate heights.

A Way of Thinking

“Engineering teaches you to ask questions, solve problems, and not always accept things at face value,” says Splinter, of Applied Materials, who has two electrical engineering degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Of course, solving problems is a task that preoccupies many a top executive. Chris Caplice, executive director of MIT’s master of engineering in logistics program recalls an old joke: Some business problems are too important to be left to business people. When engineers encounter a problem, he says, “they scope it out, pick a methodology, and then choose a solution that’s the most effective and efficient.” That’s a talent not always on display in the business world. Adds Allen: “[Engineers] have a way of thinking that’s analytical, empirical—that’s probably what sells.” It’s worth noting that struggling Ford Motor Co.—certainly in need of sound solutions to major problems—recently named an engineer as CEO: Alan Mulally, who had been a top executive at Boeing.

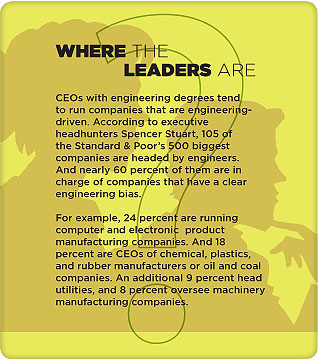

To be sure, it’s possible there’s a bias toward giving engineers the top job because the U.S. economy is somewhat dominated by companies that rely heavily on engineering. Spencer Stuart’s study indicates—not surprisingly—that many engineering CEOs lead companies that are engineering-based (see sidebar, above).

Depending on how you define an engineering-driven company, it’s arguable that slightly more than half, 260, of the S&P 500 fall into that category. But even the most engineering-reliant company wouldn’t keep an engineer in the CEO position for long if he or she were running it into the ground. So, obviously, engineers are bringing something extra to the boardroom table.

Beyond problem-solving skills, RIT’s Palmer thinks it’s focus. Engineers are trained to concentrate on the task at hand without being distracted by peripheral issues, he says. And that’s a skill they can show off early in their careers, because they’re often selected as project managers. If an engineer leads a team that achieves its goals “on budget, on time, and with results that enhance the bottom line,” he says, that gets him or her noticed. Schering-Plough CEO Fred Hassan made a similar point in a speech he gave in late 2005 to mark the 100th anniversary of Columbia University’s chemical engineering department. Hassan, who has a chemical engineering degree from London’s Imperial College, told the students that if they’re interested in management, they shouldn’t spend their entire career at company headquarters but take advantage of opportunities to work in the field. Approach field jobs “with focus and discipline,” he said. “You will get more out of it than being in a hurry to get the next job. And this will also make a good impression on your boss.”

It also helps that engineers are data-driven decision makers, Palmer says. “We ask: ‘What is the data telling us?’ We don’t allow emotions to get in the way. We weigh things on their true value, not their perceived value.” MIT’s Allen agrees. Engineering students are taught a lot of things at school they’ll never use in their careers, he says, but the payoff is, “it makes them think in a hard-nosed manner.” In business, that could mean, for example, deciding to drop formerly iconic brands or products, if research says they’re past their prime, for example, or closing plants that are no longer financially sustainable.

Tuning In to Colleagues

Office politics are a fact of life in corporate America, and executives who rise to the top need to be adroit politicians. And that’s a skill that probably has more to do with personality than training. Engineering education has long been criticized for concentrating too heavily on the sciences, without regard for business acumen or the development of “people skills.” But today that’s changing, with many top schools encouraging—or requiring—courses in communications or business management. In addition, says Palmer, engineers share a trait that can serve them well in the cut and thrust of executive-suite machinations: “One thing all engineers have in common is a sense of commitment and tenacity . . . engineers often under-promise and over-perform. It’s part of our culture. But that route can turn heads.”

CEOs ultimately are managers, requiring them to deal with large numbers—and a wide variety—of people, which requires skills well beyond the technological: an ability to communicate and work with others. Thus, says Caplice: “The best engineers have good people skills.” The stereotype of the nerdy “Dilbert” working alone is becoming a rarity. In his days as a civil engineer, Caplice often worked on road projects that required him to deal with many rival groups. “You know there are competing constituencies, and you look for solutions that satisfy the most people,” he says, which is what executives regularly have to do. Indeed, in his Columbia speech, Hassan stressed that a key communication and leadership skill is an ability to listen.

“Learn how to be ‘in tune’” with colleagues and stakeholders, he said. “This means listening and learning before you lead.” By staying in tune with his workers, Hassan has earned their loyalty and trust.

Though there are not too many engineers running companies in, say, the entertainment, food, or retail sectors, there are, of course, counterintuitive examples. The investment bank Merrill Lynch was run for several years by an engineer, Stanley O’Neil, until he was forced to step down in the wake of Merrill’s losses in the subprime loan crisis. And science-based industries are begging for executives who understand technology, according to Hassan. “There is a desperate lack of executives in large, science-centered enterprises such as ours who have scientific savvy,” he said at Columbia. Hassan adds that, like other engineers, he’s not intimidated by the science nor by the experts who work for him. “I know that I can talk with scientists about molecules . . . I can make informed decisions when we make important science-based choices.”

Multi-disciplinary Training

The current crop of CEOs tend to be in their 50s and 60s, which means they were educated at the time when engineering schools were less likely to teach the nontechnical leadership skills needed to run big companies. They had to learn them mainly on their own. Today’s students often get a broader education, learning to think about how technology and products interact with society and the environment. For example, one RIT course–Fundamentals of Sustainable Engineering–focuses on how engineering and design can affect ecosystems, public policy, and business management.

Moreover, the school’s senior design project, which all engineering students must complete as part of a multidisciplinary team, has to incorporate business planning, public policy, and environmental management. It’s also become clear to some students that an engineering degree is a great first step toward the executive suite. A growing number of undergraduates enter engineering school with management careers in mind, Palmer says, estimating that as many as 30 percent of his students want to become top managers. Additionally, as many as 25 percent of Rochester’s engineering grads are hired into leadership programs offered by companies like General Motors, Toyota, and Lockheed-Martin. These programs typically last two years and require participants to rotate through various departments, while also taking leadership courses.

That bodes well for the future. MIT’s Allen initially may have been surprised that so many of today’s largest corporations are run by engineers. But given the way engineering schools increasingly stress skills that transcend the foundation of math, science, and technology, Allen expects the trend toward the top to continue. A generation from now, he predicts, even greater numbers of America’s biggest corporations will be helmed by engineers. And just think of the Harvard M.B.A.s they’ll be bossing around.

Thomas K. Grose is a freelance journalist based in the United Kingdom.

Category: Features