The Science of FUN

By Thomas K. Grose

ENGINEERS KNOW HOW TO HAVE A GOOD TIME. JUST LOOK AT ALL THE ENTERTAINMENT ENGINEERING PROGRAMS SPROUTING UP AROUND THE COUNTRY.

The fierce steam-covered head of a dragon rose ominously from its berth on the stage of the Mirage Hotel in Las Vegas to spew real fire and sparks into the cowering, screaming audience. Then, wobbling feebly from side to side, the head snapped off and rolled into gasping onlookers as distraught on-stage magicians watched helplessly. “That,” Robert Boehm said to himself, “seems like a controls problem.”

For the next 14 years, as a mechanical engineering professor at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas (UNLV), Boehm went behind the scenes at many of the city’s increasingly lavish and technically complex entertainment shows, but he never forgot the dragon head. That is one of the reasons Boehm, along with a growing number of educators, is convinced that a degree blending art and engineering—entertainment technology—can help to meet the challenge of a worldwide entertainment revolution.

Theme parks, sports venues, and theater productions have morphed special effects, robotics, sound systems, and animation into a booming business.

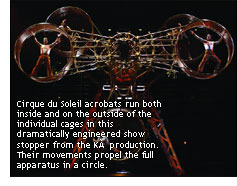

The Las Vegas market alone is sustaining nearly $1 billion in production costs for three state-of-the-art entertainment extravaganzas: MGM Grand’s new Cirque du Soleil “KÀ” production, Caesars Palace’s year-old Celine Dion show, and The Venetian’s “Phantom of the Opera.”

The video game industry, nonexistent 25 years ago, now commands an amazing $18 billion market worldwide. It’s estimated that 145 million Americans play computer and video games. The industry has the potential to add 5,000 new jobs annually.

As Americans and the rest of the world have come to expect entertainment at every level of society, from shopping malls to museums, the staggering technical challenges have fueled the need for a hybrid artist/engineer. And for those schools looking for guidance in this new field, there is a star to follow.

You can’t get much farther psychologically from Las Vegas than Pittsburgh, but that is exactly where new ground in entertainment technology education was broken. Five years ago, Carnegie Mellon University fine arts professor Don Marinelli and computer science professor Robert Pausch started the two-year master of entertainment technology degree program. “Don Marinelli is spectacular, but he is everything I am not,” Pausch says. “And that’s a tangible signal to our students that you should be able to work with people who are radically different than you are.”

Pausch says the Entertainment Technology Center (ETC) is merely the most aggressive example of Carnegie Mellon’s history of putting disciplines together in unusual ways. “We have some of the best fine art and best technology education in the world under one roof,” he says, “so when there are all these signals in the world to put those together, we walk the walk instead of talking the talk.”

The basic mantra of the program is: Everybody is an equal partner. Of the roughly 50 students admitted each year, half are from the technology field and half from the nontechnology. “We created something that forces artists and engineers to work together,” Pausch says.

For starters, that means no traditional methods. No lectures. No regular classes. No separation. The curriculum is purely project-based. Four semesters long, the program’s courses are highly unconventional. They include: Visual Story, learning the basics of visual language from film and how it applies to interactive media; Introduction to Entertainment Technology, a dramatic analysis of video games; and Building Virtual Worlds, five different team challenges in building a virtual reality project. Field trips include the Cruise to Nowhere, a three-day boat trip simulating total immersion in an experience that students must evaluate in an essay; and a trip to California to visit entertainment big shots Industrial Light and Magic, Disney Imagineering, and Rock Star Entertainment.

For the last three semesters, students are assigned to teams of four, five, or six students with a faculty member in which their only goal is completing a big project. This, Pausch and Marinelli say, is the heart of the whole course. “You give them a problem that is so hard it requires all of their skills to solve it, and you give them no time. At that point, they’re in the foxhole together,” Pausch says. They must produce an entertainment experience ready to go, work that stands alone.

Two of the projects are HazMat, which uses video-game methods to simulate tactical situations in training the New York City antiterrorism teams, and the Augumented Cognition Group, which involves creating a wireless virtual environment to enhance foot soldiers’ experience in combat.

In addition to an aggregate grade and individual grades on the projects, students meet with faculty members three times each semester for feedback on their attitudes, their interaction with other students in the program, and the way they present themselves. “We tell them, ‘This is what your boss would say to his or her spouse about you,’ ” Pausch says.

The ETC degree program achieves virtually full employment, with the giant video game company Electronic Arts hiring almost 40 percent of the graduating class in the past two years, a fact that Pausch says underscores the program’s focus on employment rather than faculty research. ETC’s good relationships with industry leaders Electronic Arts and Disney Imagineering include written agreements for hiring at least 10 interns a year. While more than 50 percent of ETC graduates work in the video-game industry, the remainder work in museums, higher education, and nonprofit fields. “They apply the principles of creating entertainment content toward noble goals as well as commercial goals,” Pausch says.

Location, Location, Location

Within high-heel walking distance of the “Strip” in Sin City, the University of Nevada-Las Vegas is hoping to establish an undergraduate degree in entertainment technology for two reasons: A ballooning market for designers grounded in technical problem solving, and elevation of the 1,500-student university to national recognition. “Las Vegas is probably the biggest lab for entertainment engineering in the country,” says Dean Eric Sandgren, who himself will teach a visualization course. Mechanical engineering professor Boehm, an ardent supporter of the courses being offered at UNLV, agrees. “Theater people believe anything can be done, and engineers anticipate problems, so putting them together gives you the best of both worlds.”

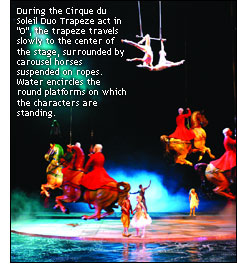

“The technology is enormous,” says Anthony Ricotta, production manager for the world-famous “O” Cirque du Soleil show at the Bellagio Hotel in Vegas. A 1.5 million-gallon pool with an internal elevator that can rise 25 feet in eight seconds was built to specs for the jaw-dropping show. “Today’s scenic elements have to be such a big ‘Wow,’ no one really knows whether they will work until they’re built.” That, Ricotta says, is where entertainment and engineering merge for the future. “Theater engineering has always been clunky and noisy, when it should look like magic.”

Support for the UNLV program and others like it is strong within the entertainment industry. Kent Bingham, president and CEO of Entertainment Engineering Inc. of Burbank, Calif., helped formulate the program’s curriculum and has been a guest lecturer. A Berkeley-trained civil engineer, Bingham was chief structural engineer for Disney’s Epcot Center and has worked on some of Las Vegas’ biggest lures. Bingham says the program at UNLV illustrates the most important lesson an engineer can learn. “Imagination is like a sleeping giant which, when awakened, lets you do things that normal architects and engineers cannot.”

At the University of Missouri-Rolla, a new program combining the performing arts and engineering will enroll its first students in fall 2005. Dean Robert Mitchell thinks the program could draw more students into engineering, including women. “They follow their passions,” he says of prospective students, citing a student who loved calculus and explosives who came to him and asked if the program would cover special effects. “Edison would be overwhelmed,” he laughs.

Interdisciplinary programs such as SUDAC at Stanford University, the MIT Media Laboratory, and Georgia Tech’s Information, Design & Technology are all highly regarded and thriving. Areas of specialty such as animation, digital media, gaming, themed entertainment, and virtual reality are targeted by programs at the University of Pennsylvania, Rensselaer, University of Southern California, and Purdue, among many others.

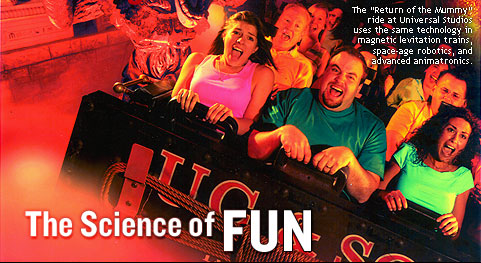

As the worlds of entertainment and technology expand and merge, opportunities for engineers grow exponentially. Jim Seay, the 44-year-old president and owner of theme-park ride and design firm Premier Rides in Millersville, Md., is a at the forefront of this new universe. A Cornell engineering graduate, he worked in the aerospace industry until the bubble burst in the ’80s and designers of cruise missiles moved to Disney to become Imagineers. Seay hooked up with the company that developed Six Flags theme parks and 10 years ago started his own firm, a wildly successful venture that has brought him international recognition for, among other designs, the “Return of the Mummy” ride at Universal Studios in Orlando and in Hollywood. Using the same technology used in futuristic magnetic levitation trains, the ride’s linear induction motors blast riders 1.5Gs uphill through 2,000-degree fire, with space-age robotics, ultraviolet black light technology, projected CGI animation, and advanced animatronics.

Seay applauds the increase in entertainment technology training. “Those who aspire to that kind of degree have the ability to be creative technical leaders,” he says. Seay’s firm is part of the Cornell internship program, and some of the students have been hired for his unique enterprise. “We’re up there interviewing right alongside IBM,” Seay notes, “and our salaries are competitive.” The world is changing by the second, Seay says, citing his daily instant messages to his newly opened office in Beijing. “It’s hard to comprehend the development happening there, and how educated the Chinese are about entertainment possibilities.”

The future for the right engineers in a country of more than a billion people? That, as they say, is entertainment.

Linda Creighton is a freelance writer based in Arlington, Va.

Category: Teaching