Offshore Tutoring + Shrinking Water Supplies + Brain Magnets

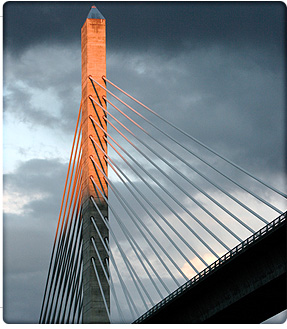

Maine has a new tourist attraction that’s also an engineering wonder: the $89 million Penobscot Narrows Bridge and Observatory, which arches across the river some 20 miles south of Bangor. The 2,120-foot-long bridge and observation tower is the first of its kind in the U.S. and only the third in the world. The 420-foot tower is, like its inspiration, the Washington Monument, an obelisk. It houses a 360-degree observation room that affords views of Maine’s rugged, mountainous countryside, up to 100 miles away.

The Penobscot span is a cable-stayed bridge: the stays holding up the deck are attached to the two pylons, instead of looping over them. But it also uses a new cradle system in which the individual cables inside each stay run through their own sleeve pipes rather than being bundled together. That means they’re parallel to, and slightly spaced apart from, one another. The cradle design allows for longer, stronger stays, thus longer bridges. It also makes it easier to inspect and replace individual cable strands within each stay. Penobscot’s stays, which include carbon-composite cables, should prove to be longer-lasting than steel strands. Engineering aside, the bridge is a lovely sight. It’s no stretch to imagine it will be a popular destination. —Thomas K. Grose

At the start of one of his physics lectures, Glenn W. Ellis, an associate professor of civil engineering at Smith College, challenged his students to walk across some styrofoam he had laid between two tables. Naturally, they all declined. And by doing so, they proved they instinctively understood some key engineering principals, including geometry, material behavior and weight loading, he told them. He then taught them the math that explained why their instincts were right. Ellis’ teaching methods earned him one of four national “Professors of the Year” awards handed out late last year by the Council for Advancement and Support of Education and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The winners were selected from a field of 300 nominees.

Ellis joined Smith in 2001 to help launch the first engineering program created expressly for women, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education. In his acceptance speech, he stressed that it’s important to respect students because they’re capable of amazing results. “While we do owe it to them to be scholars in our own subject areas, it is to me a contradiction to value our own scholarship and at the same disregard the research on learning. It is just not good enough to teach them the way that we were taught. We know that doing so in engineering will surely exclude many of the young people we need to attract.” —TG

SCOTLAND—Ten of Scotland’s top universities are pooling their resources to form the Scottish Research Partnership in Engineering, which begins life with initial funding of around $260.6 million. The partnership’s goal is to “ensure Scotland’s future as a driving force in engineering.” Around $54.6 million of the money comes from the Scottish Further and Higher Education Funding Council (SFC). The remaining money will come from the participating universities, invested over the next five years. Member schools include Heriot-Watt University and the universities of Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dundee. The partnership expects to fund the addition of 69 new academic posts, supported by 71 Ph.D. students and research assistants. SFC Chairman John McClelland says, “Scotland’s universities now have a combined research strength to compete with the world’s very best in engineering.”—TG

Infants driving motorized kiddie cars and navigating them with joysticks? It could be mayhem. But a tiny-tot vehicle developed by researchers at the University of Delaware is also a robot fitted with smart sensors. It can determine where obstacles are and, depending on what they are, allow the baby driver to either bump into them, or take temporary control and steer around them. Though it sounds like fun, this smart cart isn’t a toy. It has a serious purpose: helping infants with special needs improve their cognitive development. After birth, the experiences we encounter exploring our world help with the early development of our brains. But infants with disorders such as Down Syndrome, cerebral palsy and autism often have limited mobility, which can further slow their already delayed development. The main reason assistive technology, such as powered carts, hasn’t been used for infants before was safety. There were understandable fears that children would crash into dangerous obstacles or dash out into roads.

The Delaware prototype cart, called UD1, “addresses each of these safety issues so that infants have the opportunity to be a part of the real-world environment,” says Sunil Agrawal, the mechanical engineering professor whose small robots provided the key technologies for the kiddie cars.

Future versions will also allow parents or supervising adults to use remote control to override the robot. The project is truly interdisciplinary, bringing together researchers in engineering, early-childhood development and pediatric therapy. Ultimately, the team envisions robotic baby cars that are lightweight and stowable in car trunks, yet sturdy enough for outdoor play.

Imagine: getting your first set of wheels at seven months.—TG

After three years of declines, the number of foreign students studying at American universities increased in 2006 by 3.2 percent to a total of 582,984, according to the annual Open Doors survey published by the Institute of International Education. That’s close to the high-water mark of 586,323 set in 2002. After several years of annual gains between 1997 and 2001, foreign student enrollment inched up only marginally in 2002, after which it fell for several years. Initially, the main reason for the decline was tighter U.S. visa rules implemented after the September 2001 terrorist attacks, which caused both confusion and long delays. One reason cited for the new gains is a visa application process that’s now easier for applicants to navigate. Foreign student enrollment in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) was a mixed picture. While 63 percent of schools reported no change in STEM enrollments, 28 percent saw an increase. Only 9 percent reported a decline. The University of California, Los Angeles, attracted the most foreign students: 7,115, or 21.3 percent of its total student population. Columbia and New York universities were second and third, with 5,937 and 5,827 foreign students, respectively.—TG

Nearly 40 percent of the world’s population lives less than 100 miles from a shoreline, areas generally defined as coastal. And because of global warming, they may be at risk of losing up to 50 percent more of their freshwater supplies than previously predicted, according to a new Ohio State University study based on simulations.

OSU geologists used data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that indicate sea levels could rise as much as 23 inches over the next 100 years. As the rising sea water covers more land, it will also contaminate underground freshwater aquifers, creating undrinkable brackish water. It had been assumed that as the seas came inland, the salt water would penetrate below ground only as far as it moved inland above ground. But the OSU simulations found that, depending on the types of sand involved, brackish water can penetrate aquifers up to 50 percent further inland than the seawater itself reaches. Some of the most vulnerable areas—the U.S. East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico—are also some of the most populated. —TG

Roadside bombs and mines have proved particularly deadly to U.S. forces in Iraq, and devilishly difficult to detect. Satellites, spy planes and unmanned drones fitted with electro-optical and infrared sensors were put into use to locate the devices, but had a success rate of around nil. That’s now changed, thanks to algorithms created by Joshua R. Fairley, an electrical engineer at the Army’s Engineer Research and Development Center in Vicksburg, Miss. Fairley, 34, who is a graduate of Mississippi State University, used the center’s Cray XT3 supercomputer, which can perform 40 trillion calculations a second to create a detailed, 3-dimensional virtual world that mimics the harsh conditions in war-torn Iraq, right down to the soil, asphalt and concrete that can give bombs cover. He tested the sensors in that computer-generated world to see how they were affected by conditions ranging from weather to time of day. The result: sensors that are now accurate 75 percent of the time. And Fairley believes accuracy can be improved to 90 percent. “What we are trying to do in our work is to inform our commanders on what are the most optimal sensors to use, given the environment . . . and time of day,” he told the Washington Post. And that’s a formula for saving lives— TG

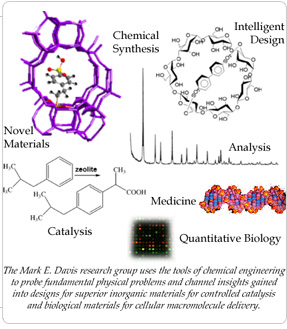

Cancer patients who have to undergo chemotherapy suffer horribly from harsh side effects, including hair loss and nausea. That’s because chemotherapy drugs destroy healthy tissue as well as the cancer cells that create tumors. The wrenching effects of these drugs are why they have to be used in moderation, which limits their effectiveness. In 1996, when his wife had to undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer, Mark Davis was motivated to find a better way. He’s a chemical engineer at the California Institute of Technology, and an expert at assembling nanoparticles. More than a decade later, Davis’ research looks extremely promising. His solution bonds the molecules of strong chemo drug camptothecin with those of a starch-based polymer. The resulting molecules are able to pass through the more porous veins and capillaries of tumors, but at 40 nanometers—about one-thousandth the diameter of a human hair—are too big to pass through the blood vessels of healthy tissue. The drug, IT-101, has worked amazingly well in the first phase of chemical trials, effectively treating an apparently fatal case of pancreatic cancer, as well as large lung and kidney tumors. Davis needs to move on to the second phase of the trials, but news reports of his initial successes have led to his being inundated with calls for help. He’s stopped answering his phone, he told Newsweek, “because I can’t keep saying no to people.” He finds that heart-wrenching, but Davis also knows his invention must soon advance to the second phase—because the statistical evidence that results from it will prove if the nano-med he’s sculpted truly is a lifesaver. —TG

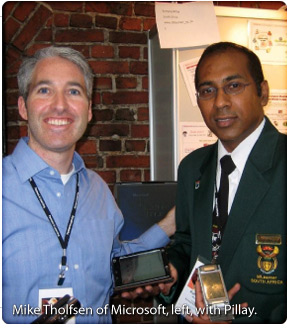

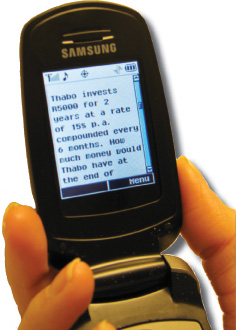

SOUTH AFRICA—About half of Kumaras Pillay’s high school students in Durban, South Africa, live in shacks with no electricity. Yet they are perhaps more likely to access math and science information from home via the Internet than rich kids with PCs in their bedrooms.

Pillay made this possible by creating a tutoring website specifically designed to be accessed on cellular phones. A math and science teacher who earned a mechanical engineering degree before finding his calling in education, Pillay is not just helping his own students. In the first 8 weeks after he launched www.mlearner.co.za in September, the site received 180,000 hits from 11th and 12th grade pupils all around South Africa. “We were starting to believe we had a product that is really going to revolutionize education,” says Pillay.

Others have also become believers. In October, Microsoft awarded Pillay and MLearner first prize ahead of more than 100,000 other applicants at their Innovative Teachers’ Forum Awards in Helsinki, Finland. The honor has emboldened Pillay to go international. He is meeting with top math and science teachers from around the globe who will contribute tests and other materials to MLearner.

Pillay’s innovation stems from what he saw around him when he arrived at Durban’s Burnwood Secondary School. Burnwood was Exhibit A in what Pillay calls “a national crisis in math and science.” Fewer than a third of all graduates in the KwaZulu-Natal province pass the national exams in mathematics. Many at Burnwood had gone long periods without a math teacher at all. The nation’s elite, says Pillay, “have private tuition, tutors and study guides, but the majority are shortchanged.”

Pillay noticed, however, that most of his students carried a cell phone, which are inexpensive and widely used in South Africa. He realized that this device could bridge the divide, and enlisted his principal, Vanesh Gokal, to write the software. Students can now download a few pages of information for about a penny in phone charges. They can even discuss their work with fellow pupils and teachers in chat rooms. “It’s an attempt to level the playing field,” says Pillay, “quality education should not be a privilege; it should be a right for all.” —Don Boroughs

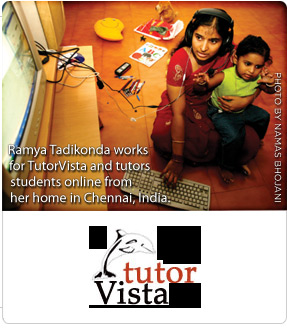

Call it “distance learning meets off-shoring.” The same kinds of technologies that allowed American companies to move call centers and back-office operations to India are now being used to exploit a lucrative and growing tutoring market. And because the cost of getting tutorial aid from India is relatively cheap, new India-based companies are bringing online tutoring—once a luxury for only the fairly well-off—to the masses. A typical U.S. service costs at least $40 an hour. But TutorVista, a two-year-old company started by entrepreneur Krishnan Ganesh, an Indian call center pioneer, charges clients just $99 a month for unlimited access to its tutors. TutorVista of Bangalore offers help in English, math and science to students as young as 6. It was expected to have a teaching staff of around 1,200 by the start of this year. Most of its tutors have master’s degrees and an average of 10 years’ experience. TutorVista requires them to undergo another 60 hours of training.

Students and tutors talk via voice-over-Internet technologies, and also make use of instant messaging services and virtual whiteboards.

TutorVista—which raised more than $15 million from venture-capital companies and other investors—so far has around 10,000 U.S. clients, but hopes to reach a million. Rival Educomp Solutions, based in New Delhi, says the U.S. tutor market could be worth $8 billion. Let the lessons begin. —TG

Will scientists one day be able to use magnetic fields to reengineer how our brains work? Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) uses a device that sends a magnetic field into the brain that can be used to agitate neurons in the brain’s processing centers, thus activating, manipulating or stopping various brain activities. Some researchers believe TMS may prove an effective means to control depression, particularly in patients who’ve grown immune to drug therapies. Indeed, early this year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is expected to rule on the use of TMS devices to treat depression. Other potential uses include easing the tremors of Parkinson’s patients or subduing pain—particularly that of migraine sufferers. Lincoln Kim, a life-sciences analyst at Toronto’s MaRS Venture group, which seeks to commercialize new technologies, wrote in a recent blog that a demonstration of TMS he saw at the Neuro2007 conference in Tokyo was impressive. Beyond the potential therapies, writes Kim: “ . . . it may one day be possible for us to learn how to utilize more than 10 percent of our brain. Now that would be interesting . . . .” —TG

Category: Briefings