DISSECTING DISASTER

+ BY LUCILLE CRAFT

+ PHOTO CREDITS: KYODO / AP IMAGES; RIGHT: AP PHOTO / YASUSHI KANNO, THE YOMIURI SHIMBUN

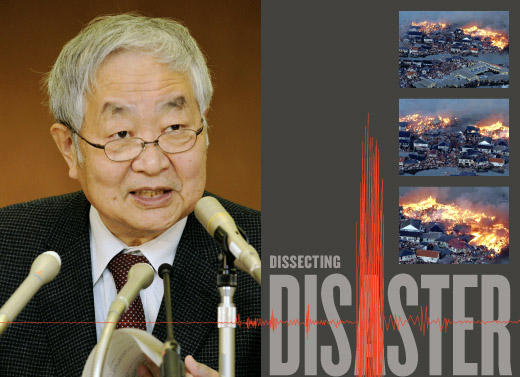

After the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, as in past accidents, Japan turned to mechanical engineer Yotaro Hatamura to unravel a chain of mistakes.

TOKYO – It was weeks after the March 11 disaster. Tens of thousands were in homeless shelters. Radiation continued to leak from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Public faith in government had hit a nadir. After dissembling about the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl, Japanese officials realized the recovery had to start with a brutally honest reckoning, from investigators beholden to neither the powerful nuclear industry nor its increasingly vocal foes.

So instead of nuclear specialists, they recruited a Fukushima town mayor, a few lawyers, even a novelist. For the chairman’s post, the choice was obvious. As Japan had so many times in the past after a horrendous disaster or accident, it summoned a man with a passion for dispassionately unraveling the chain of mistakes. Whether food contamination or crashing elevators, train derailments or collapsing tunnels, Yotaro Hatamura is Japan’s Mr. Accident, a mechanical engineer who has devoted his life to revealing how and why things go awry.

“There’s probably no other person who could do a good job,” says Kenji Iino, a colleague at the elite University of Tokyo and cofounder, with Hatamura, of the nonprofit Association for the Study of Failure. “There are a lot of other professors who have experience in nuclear engineering. But they would probably lose the big picture.”

Blame Is Not the Point

Hatamura, 70, created the niche science of shippaigaku, or “learning from failure,” dissecting disasters for clues to guard against their recurrence. If this sounds like a CSI procedural, the similarities are superficial. In Hatamura’s book, looking for culprits in a disaster is the worst way to get at the cause.

In an address to the Japan National Press Club in June 2011, Hatamura explained his ground rules: “Blaming individuals leads us to the conclusion that without those people in charge, the nuclear accident wouldn’t have happened. But I believe that even with different actors, the result would have been the same.”

Not everyone is enamored of Hatamura’s take-no-culprits ethos. The Japanese Diet, or parliament, commissioned a separate inquiry that is the antithesis of the Hatamura approach, led by another Tokyo University emeritus scholar, physician Kiyoshi Kurokawa. His panel is openly partisan, with antinuclear and technically experienced members. Unlike Hatamura’s closed sessions, Kurokawa’s interviews are public, and the panel has subpoena power. The group has revealed that the government’s system for predicting radiation contamination, known as SPEEDI, was made available to the U.S. military shortly after the accident but not until much later to local residents, who could have been guided away from toxic areas to safety.

While public naming and shaming are probably inevitable in the face of such immense suffering, Hatamura argues that intimidation doesn’t yield the best results and that even without coercion, the truth will out.

“We point to where technical failure happened,” says Iino simply. “It’s not our role to say who was responsible.”

Hatamura, who declined to be interviewed for this article, is now retired but was literally a larger-than-life presence on the leafy and idyllic downtown campus of Tokyo University. Built like a linebacker, with a no-nonsense temperament to match, he had a knack for terrifying undergraduates in the engineering department. His sense of personal ethics became legendary one day, when he got wind that a corporate recruiter was trying to woo his students with a free meal. Hatamura burst into the room. “WHO’S GOING TO LUNCH?” he yelled. Needless to say, no one did.

And yet, Hatamura was a popular professor who quickly grasped that the most engrossing part of his lectures wasn’t dry sermons on what to do right – but sometimes painful, true-life tales of what went wrong. The centerpiece of his courses was a unique and engrossing 10-hour section that taught safety by recalling dozens of case studies, complete with names, where upperclassmen had goofed up in spectacular fashion. In summer retreats, students were even encouraged to seek out the protagonists to discuss their embarrassing episodes in detail. Putting a face to these hard-won safety lessons, says Iino, was a mnemonic tool. “People are very good at remembering people’s faces,” says Iino. “For some reason, the human mind works better if anything is associated with a human, rather than an object.”

A former student of Hatamura himself, Iino recalls a story about an assignment that called for pouring melted aluminum into a steel frame. Patched with clay, the mold had to be prepared in advance, carefully dried to eliminate any moisture. When one student neglected to dry his frame thoroughly, his aluminum blasted into the air – and then dropped on his head, singeing off the student’s hair. He survived, only to be immortalized in Hatamura’s lectures. Students were even escorted to that fateful lab, where the ceiling still bears signs of the explosion.

Hatamura, a former manufacturing design engineer with the industrial conglomerate Hitachi, recalled in his Japan Press Club speech how “learning from failure” was born: “When I discussed design with my students, I began to talk about my mistakes: how a fire started and I thought I’d be killed. My students were rapt, fascinated to hear about how their professor had screwed up. Because it could just as easily have happened to them. This method inoculates them against trouble and cultivates an independent judgment ability – a skill that will serve them for life.”

Seat of the Pants

While his country was sure it wanted him at the helm of the Fukushima Daiichi investigation, the professor himself was consumed with ambivalence about signing on for perhaps the most important and difficult chapter of his storied career. “Honestly, I accepted with reluctance,” he told the Japan Press Club. “But running away, I thought, would be irresponsible.

“If we don’t learn from this terrible accident, it would be unforgivable. So I accepted the post. But I was at a total loss about how to proceed. So it’s been seat of the pants.”

It’s the engineer’s job, Iino says, to anticipate and mitigate our own human error: “We have to understand people can make careless mistakes.” In the absence of outright malice, accidents usually are the product of design or organizational flaws.

A fatalistic refrain heard repeatedly after the reactors blew up in Fukushima – that because the earthquake and tsunami were “beyond our expectations” their designers were off the hook – is a familiar but unacceptable excuse to accident experts like Hatamura. “Engineers should be ashamed if something happens that they didn’t expect,” says Iino. “They should have prepared better.”

After interviews with 456 witnesses and 900 hours of testimony, the Hatamura panel produced a 507-page interim report in December; its final report is due in the summer. The initial findings, based on accounts from workers at the plant as well as officials in Tokyo, are a damning indictment of both the utility, Tokyo Electric Power, or Tepco, and its regulators. The report portrays the leadership in chaos, watching helplessly as two reactors exploded, radiation spewed into the atmosphere, and three reactors went into meltdown at Fukushima Daiichi, 140 miles away.

Tepco was especially taken to task for failing to design and plan for an extraordinary magnitude-9 earthquake and massive tsunami. Despite expert warnings for years that the area was vulnerable to high waves, Fukushima Daiichi was built to withstand only 20-foot tsunamis. The March 11 tsunami reached 49 feet, wiping out the plant’s emergency electrical system, which left the reactors without a cooling system and triggered the meltdowns.

Fleeing into Danger

Perhaps the worst aspect of the bumbling and often ineffective response to the Fukushima accident was the delayed and confused evacuation of the 110,000 residents of eastern Fukushima. In the absence of any clear directive from the central government — in part because communications had been severed by the earthquake, in part because no one had ever thought to plan for a mass evacuation 20 miles beyond the plant – most of the local towns around Fukushima Daiichi ended up evacuating on their own. The report noted, as residents suspected early in the crisis, the government was more concerned with panic control than with keeping frightened citizens in the loop. In at least one town, Namie, residents ended up driving straight into the plume of radiation carried by northwest winds.

While the government declared Fukushima Daiichi stable in a state of “cold shutdown” in December, the Hatamura panel notes that the disaster is far from over, with continuing fears and uncertainty about the food, water, and air in Fukushima. The government concedes that part of Fukushima, once a fertile agricultural region famous for its peaches and rice, may be uninhabitable for generations.

“We must approach this tragedy as a priceless lesson,” Hatamura has said. “The ‘tuition’ is steep. But the potential payoff could be equally valuable.”

Lucille Craft is a freelance writer based in Tokyo.

A summary of the Hatamura panel’s interim report is at

http://icanps.go.jp/eng/120224SummaryEng.pdf.

Category: Features