September 2009 – Feature

BY THOMAS K. GROSE

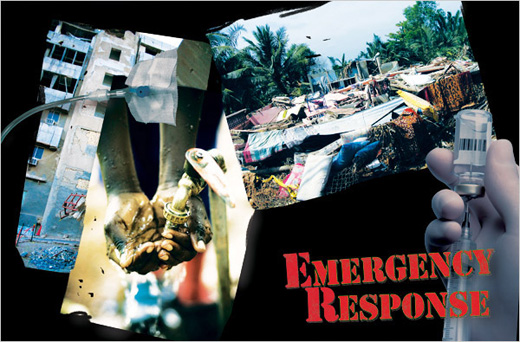

EMERGENCY RESPONSE

Crisis engineers bring needed skills and order to disaster zones, easing victims’ plight with water, shelter, and sanitation systems.

LONDON — Soon after a devastating cyclone struck the Southeast Asian country of Myanmar (Burma) in early May 2008, killing around 150,000 people, British civil engineer Paul Jawor packed his bags and grabbed his passport. Taking a month-long leave from his job as a highway engineer in southeast England, Jawor hired on as a water sanitation specialist with Médecins Sans Frontières — also known as Doctors Without Borders — and headed to Myanmar’s Irrawaddy Delta, one of the worst-hit areas. There he quickly devised ways to give 25,000 disaster victims life-saving potable water and helped organize deliveries of rice.

Jawor, 44, was a good choice for the job. He’s an experienced humanitarian engineer who, since 1999, has been regularly parachuting into crises. And MSF knew his credentials were impeccable, as Jawor is a member of the international disaster relief organization RedR. For nearly 30 years, London-based RedR has been recruiting and giving expert training to those engineers and other professionals willing to rush to work in disaster zones, both natural and manmade. Since 1980, 2,500 RedR members have been dispatched to nearly every major humanitarian crisis that’s erupted around the world, from famines to earthquakes to floods to war. It’s not duty for the faint of heart. Jawor’s own roster of hot spots includes Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Kashmir, and Angola. As he notes, “People tend to not go on holidays to the places I’ve worked.”

Unlike groups like Engineers Without Borders, which are development-project based, “we are disaster-relief based,” explains Sarah Milnes, RedR’s communications director. RedR is the go-to clearinghouse when the big aid agencies like Oxfam and MSF need to quickly find engineers experienced in providing emergency assistance. RedR members’ salaries – from $29,500 to nearly $66,000 on an annual basis – are paid by the aid agencies that hire them. The agencies pay an additional fee to RedR of 5.5 to 10 percent of the member’s salary. These fees, plus fundraising, cover RedR’s operating costs.

There are currently 1,700 members in RedR’s register, not all of whom are British. And though it includes other professionals – healthcare workers, humanitarian coordinators, surveyors, and architects among them – engineers comprise 70 percent of the membership.

Though some RedR members maintain private-sector jobs and take on overseas aid assignments when they can arrange leaves of absence, most are paid, professional aid workers. “To do relief work, you generally need professional expertise,” Milnes explains. “The sector is more professionalized than people realize. That’s why we exist; we have the right skills on offer.” Many members work in disaster relief for no more than six months at a stretch, spending the majority of their time on less stressful development projects. That’s how Jawor structured his career before recently returning to England, taking the highway job to be closer to his elderly parents. “You can’t do it totally full-time,” he says of the grim chores that face professional aid workers. “That would really suck out your humanity.”

Aside from recruitment, RedR concentrates on providing training courses geared toward disaster-zone contingencies, particularly in the areas of engineering, health, and security. Beyond training its own members, RedR is regularly contracted by other aid agencies to train workers in courses such as Public Health in Emergencies and Managing Projects in Emergencies, as well as in workshops on shelter essentials. Outside Britain, RedR runs courses for local residents and nongovernmental organization employees in Sudan and Sri Lanka. The former focuses on security, the latter on disaster preparedness. According to Jawor, RedR training is the gold standard. When he comes across other professionals in the field who have undergone the training, there’s an immediate bond, “because you know they know what they’re doing.”

Originally called the Register of Engineers for Disaster Relief, RedR was the brainchild of Peter Guthrie, now a professor of engineering for sustainable development at the University of Cambridge. In 1979, Oxfam asked him to help with its efforts to ease the refugee crisis in Malaysia caused by the huge influx of Vietnamese “boat people.” Guthrie came away from that experience with the realization that there’s a great need for engineers in disaster zones – a novel notion at the time. “When RedR was set up, no one thought of sending engineers into the field,” says Robert Hodgson, the sixth engineer to join the fledgling charity back in 1980, and now its chair. But doctors and nurses who ventured into emergency zones soon found that engineers were needed, he adds, “because they knew they were wasting their time if they didn’t have clean water.”

A 100-Foot Long Pit

Since then, the U.K. operation has grown into a major nonprofit with a $4.5 million budget and a royal seal of approval: Princess Anne is the group’s president. Funding comes from a variety of sources, including large engineering firms like Arup Group and Black & Veatch, as well as from charitable trusts and various engineering associations. Moreover, RedR has also gone global, with autonomous chapters around the world – Australia, Canada, India, and New Zealand. RedR International, the umbrella association headquartered in Geneva, monitors this coalition of national RedRs and manages an accreditation process.

RedR’s engineering membership tends to be heavy with civil and environmental experts. In part, that’s because the most urgent needs in emergency zones are water and sanitation, and then shelter. “You need to ensure adequate sanitation,” says Toby Gould, who oversees RedR’s principal training programs. “It becomes a major killer if it is not addressed early on.” When Jawor arrived in Myanmar, for example, he found that most wells had been severely polluted by seawater. So he used plastic sheets attached to roofs to collect rainwater for drinking. He then organized the digging of a pit 100 feet long, 20 feet wide, and a foot deep, which he lined with plastic to collect even more rain. “It looked like a swimming pool, but it worked.” Beyond the civils, RedR welcomes engineers from all fields to meet the host of disaster needs, including maintenance and logistics. “It’s not the discipline, it’s about how all engineers approach problem-solving,” Hodgson says.

Gould concurs: When there’s a need to quickly bring aid to countries beset by nature or mankind run amok, “problem-solving is a major part of the effort. It’s not rocket science, but it helps to have an engineering mind. It’s all about finding practical solutions that can work quickly.” In addition, “engineers typically make excellent project managers,” says Gould, who holds a degree in civil engineering and a master’s in water engineering. Since he joined RedR 15 years ago, he’s been deployed to Rwanda, Ethiopia, Iraq, and Kosovo. Jawor notes that “it’s about approaching things in a logical manner.” Yet disaster relief also requires engineers who can work without computers and determine how to construct useful devices from nothing more than plastic sheets and scraps of wood. In Zimbabwe, Jawor organized the construction of a hospital built solely of mud bricks for walls, cow dung for floors, and grass for roofs. “I’ve never done such complicated engineering in my life,” he says.

Danger Is Never Far Away

Beyond training and ingenuity, humanitarian engineers have to cope with human misery on a massive scale. After the catastrpophic tsunami that struck the Indian Ocean on Dec. 26, 2004, leaving behind a huge swath of death and destruction, Jawor was dispatched to Sri Lanka. He spent the first two weeks pulling dead bodies from the debris before he could even focus on any relief projects. Many survivors were badly traumatized, so to keep them constructively occupied, Jawor’s team paid them to collect bricks from their ruined homes – then eventually returned the bricks to them to help rebuild the houses. At times, the tasks that await engineers in disaster zones can seem overwhelming. Sent to Rwanda during the refugee crisis triggered by that country’s genocidal 1994 civil war, Gould was the sole engineer in a camp of 50,000 – few of whom spoke English. It came down to him to devise and construct a workable water system, while all around, people were dying from dehydration. “It is hard at times to deal with all the suffering,” he says. “So you concentrate on the tech side of things when the personal side gets too difficult.”

Danger is never far away, either, which is why RedR conducts training in such skills as avoiding abduction and surviving carjackings. “Security is a big issue,” says Hodgson, noting the upsurge in recent years of aid workers targeted in conflict zones. Not long ago, a RedR-trained NGO field officer traveling in Darfur was ambushed by five armed men who robbed him and his colleagues, beating them with sticks.

Despite the desolation, frustration, and risks involved, what makes the work worthwhile for RedR’s army of humanitarian engineers are the times their efforts succeed, even in small ways. “No one,” Jawor says, “can pay me enough money for the looks I get when I give someone who has lost everything a little something back.” Humanitarian engineers are often people who determine early on in life that they want to put their abilities to use where they’re most needed and can do the most good. RedR gives them ample opportunity to do just that.

Thomas K. Grose is Prism’s chief correspondent, based in the United Kingdom.

Category: Features