Getting in Gear

When American engineers talk about the need for the United States to better compete in the global economy, the discussion almost always centers on two countries: China and India. People rarely, if ever, mention another country that is geographically closer to the United States: Mexico.

Known more these days for generating conversations about illegal immigration, Mexico has quietly been building up its infrastructure over the past decade to educate more engineers and attract companies with advanced engineering design work.

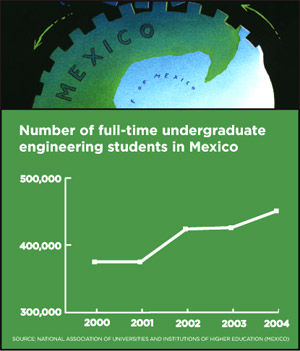

Now that investment is beginning to pay off. Some 451,000 students are currently enrolled in full-time undergraduate engineering programs in Mexico, up 20 percent since 2000, according to the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education. The would-be engineers are training on the latest equipment, much of it donated by foreign companies with manufacturing facilities in Mexico. And when they graduate, many of these students are staying close to home and getting high-skilled jobs being created by multinational companies.

All that is enough to cause yet another headache for American educators and engineers already worried about fewer foreign students studying in the U.S. and engineering jobs being outsourced to other countries. American universities enroll a little more than 370,000 engineering undergraduates, a number that has barely inched up since 2000, even as the overall number of undergraduates has grown nationwide.

“Mexico is catching up,” says Kenn Morris, director of Crossborder Business Associates, a San Diego-based research firm that focuses on providing information to U.S. and Mexican businesses and organizations looking to collaborate. “There is much more of a public interest in people there wanting to improve their quality of life, while in the U.S., there has been a flattening of the speed of innovation and education.”

Staying Home

As a result, more Mexican students, including engineering majors, are deciding to stick around for their college education rather than make the trek to the United States. That, in turn, has improved the quality of Mexico’s engineering schools, Morris says, and increases the likelihood that the students will want to remain there to work after graduation.

The numbers seem to bear that out. Enrollment of Mexican students at American universities has fallen slightly in recent years, according to “Open Doors,” an annual report on international academic mobility published by the Institute of International Education. Overall, 13,000 Mexican students were enrolled at U.S. institutions in 2004-05, a 2 percent drop from the previous year. (The tuition bill for many of those students who study engineering is paid for by Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology, in the hope that the students will eventually return home to put their skills to work.)

Two years ago, Eduardo Perez had thoughts of coming to the United States to study electrical engineering. He even visited several American universities, including Georgia Tech and the University of Florida, during a summer he spent living with an uncle in Atlanta. But the pull of his home and aging parents led him to National Polytechnic Institute in Mexico City, the country’s top engineering school.

“I didn’t know if I was really ready to go so far away,” says Perez, who is taking a break from his studies to care for his parents. Mexicans, he says, “are all about family,” and many engineering students like the fact “that they now have choices here at home.”

Even so, Perez is not giving up on studying at a college in the United States altogether. He hopes to eventually come for a shorter stint as an exchange student. He’s not alone. While engineering deans lament that they have fewer foreign students over all in recent years—in part because of the visa restrictions put in place after 9/11—they report a boom in exchange students.

The College of Engineering at San Diego State University has about 80 Mexican exchange students in any given semester, says Dean David Hayhurst. The improved academic quality of the Mexican institutions shows in the students, he adds. “They come here and do quite well,” he says.

In a global economy, Hayhurst says, it is important that engineering students experience another culture at some point during their college career. For the students from Mexico, “they learn to understand the U.S. while they are here,” he says.

Now, he says, the challenge is convincing American students the same is true for them. At San Diego State, only about a dozen students study in Mexico each semester. “Our students have phenomenal opportunities to do internships in San Diego in biotech, wireless communications and aerospace engineering,” Hayhurst says. “They don’t want to lose that by going elsewhere, even to Tijuana,” which is just 45 minutes from the university’s campus. As part of San Diego State’s new construction-engineering program, Hayhurst is weighing whether to require his students to spend a semester in Mexico in order to better understand workers on construction sites in the United States, many of whom are from south of the border.

Although engineering deans at U.S. universities say a degree from one of their institutions is still better than one from a school in Mexico, they admit that Mexican colleges do excel in some technical areas that could prove beneficial to American students. For one, the manufacturing sector is still strong in Mexico, where “maquiladoras” making everything from refrigerators to televisions line the border with the U.S. The engineering students there gain valuable skills in product manufacturing and automation by taking advantage of work in the factories and equipment donated to the colleges by corporations, which also help develop engineering courses.

“The engineers produced in Mexico have good training,” says Ricardo Dominguez, the aerospace division director at BC Manufacturing in Tijuana, which certifies the airworthiness of planes made in Mexico. “Now we just have to convince companies around the globe of that.”

A Hiring Spree

In many places, they are already convinced. Multinational companies, including GE, Siemens and Honeywell, that once located facilities in Mexico to produce products are now opening up small operations for design and testing work, much of which is done by engineers. GE employs more than 500 engineers at a facility in Querétaro that designs and checks jet engines. Officials there expect to hire another 200 this year.

One reason for the hiring spree? Low salaries. Engineers fresh out of college in Mexico make around $15,000 annually; compare that with their U.S. counterparts, who graduate to $45,000-a-year jobs. “We can hire a lot more people here than companies in the United States,” says Dominguez, who graduated from the National Polytechnic Institute. “Companies have figured out it’s cheaper to make things here, and now they’re figuring out it’s cheaper to design things here, too.”

Canadian aircraft manufacturer Bombardier Inc. recently opened a plant in Querétaro, where about 80 employees trained at the Universidad Tecnológica de Querétaro work, says Marc Duchesne, a spokesman for Bombardier. The company partnered with the school to develop an aerospace curriculum.

For now, Duchesne says, the school is providing space for training laboratories and classrooms until a new aerospace university is built by the Mexican government nearby. At that point, the school plans to develop partnerships with institutions worldwide to expand the scope of its aerospace curriculum.

Despite the investment by companies like Bombardier, Mexico still has too few jobs for too many engineering graduates, says German Grajeda, who is in charge of co-op programs at the National Polytechnic Institute. Those who have difficulty finding engineering positions usually end up taking other technical jobs for which they are overqualified and often paid less than what they expected. “It’s frustrating for them,” Grajeda says.

In recent years, students have started asking about jobs in the United States, a pathway Grajeda says he discourages because graduates who fail to get a job with a company in Mexico—which typically pick the top graduates—may find landing a job in the United States even harder. “They will be disappointed there, too and won’t have their family for support,” he says.

Grajeda tells his students to be patient—jobs will come as more companies learn of the growing number of engineers in Mexico. Dominguez, the aerospace engineer in Tijuana, agrees, although he is more cautious. His biggest concern is not China or India, but the United States, where President Bush has proposed doubling federal spending on research in the physical sciences, mathematics and engineering over the next decade.

Whether or not that will happen is still unclear. But Morris, the San Diego consultant, says in some ways it doesn’t matter. He believes the United States should embrace Mexico’s growing capabilities in engineering. As the world economy expands, he argues, the United States needs to partner with Mexico and Canada to retain the regional network of companies that can compete with the burgeoning research-and-development efforts underway in Asia.

“Whether we like it or not, the type of R&D capabilities that have traditionally occurred in the U.S. are happening all over the world,” Morris says. “When we offshore those activities, then the suppliers like the ones in Mexico also go. The only way we can keep all those jobs in the region is to work more closely with Mexico and Canada and not view them as competitors.”

Jeffrey Selingo is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.

Category: Features