March 2008 – Briefings

ISRAEL—Few Middle East problems lend themselves to engineering solutions. But visionaries believe one particular project could help alleviate two problems at once.

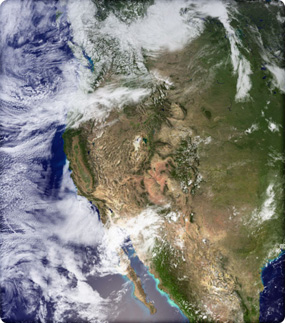

Here’s the idea: Build a canal that can carry more than 500 billion gallons of water a year from the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea toward the Dead Sea (pictured), which straddles the Jordan-Israel border. Since the Dead Sea is the lowest point on Earth, the water will plunge downward some 1,500 feet, generating pressure for desalination. In this process, the seawater will press against tubes packed with filters. Water molecules will seep through the filters, but the salt will not. Additional energy will need to be generated from a small electric plant to complete the process, but not as much as would be required without the waterfall.

Most of the desalinated water will be pumped to Jordan, with 5 to 10 percent going to the Palestinians. Unfiltered seawater will flow into the Dead Sea.

Result: Parched Jordan gets fresh water, and the Dead Sea is replenished, saving its mineral industry and tourism. Oh—and the cooperation will contribute to regional peace.

The $2 billion – $5 billion proposal has enough support to be one of the signature projects of the three-way Economic Peace Corridor launched by Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority. The World Bank is currently carrying out a two-year feasibility study.

Environmentalists think the whole idea is all wet. Drawing that amount of water from the Red Sea “will affect the currents in the Gulf and the fragile coral reefs,” says Mira Edelstein of Friends of the Earth Middle East. And the influx of seawater could disturb the unique, therapeutic mineral composition in the Dead Sea, she adds. So far, however, the feasibility study is moving forward. —Joshua Brilliant

The PBS cartoon show Curious George, which debuted in 2006, has several new episodes intended to interest 2- to 5-year-olds in engineering, math, and science. Topics include: exploring a coral reef to find a downed weather satellite, flotation and floods, simple mathematics, and measurement. In the episode shown here, the inventive monkey makes a robot outfit for himself using paper, tubes, cardboard boxes, and a colander.

Oleophobic: An unhealthy fear of margarine? No, it means oil-resistant. Scientists have long sought to develop oleophobic materials but with little success. Yet in nature, there are plenty of water-resistant materials. That’s because water has a high surface tension, so it beads up easily. But with its low surface tension, oil just soaks in. Now two researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, inspired by the repellent quality of lotus leaves, have created a material that mimics this ability but with oil. It could be used to protect rocket and airplane parts that can be ruined by fuel, like rubber gaskets and O-rings. The pair, chemical engineer Robert E. Cohen and mechanical engineer Gareth H. McKinley, both researchers at MIT, used an electrospinning process to develop a tissue-like material composed of microfibers with bumps and nubs surrounded by pockets of air—not unlike the structure of the water-dwelling lotus plant. When the oil hits the material, it forms droplets that rest atop the fibers without soaking the material. Now that’s a slick trick. —TG

How did the universe originate, and what is its fate? Is there life elsewhere in the vast reaches of space? Finally, scientists hope to answer these enduring questions with a new generation of mammoth optical infrared telescopes. Construction of the first of these ELTs (Extremely Large Telescopes) is expected to begin in two years. If an $84 million study authorized by the European Southern Observatory goes well, then work will commence on a $1.18 billion telescope later this year.

The E (for Europe)-ELT will be some 100 times larger than the biggest existing optical telescopes. It will sport a mirror that is 138 feet in diameter, composed of 908 hexagonal segments and housed in a 262-foot dome. According to the ESO, it should be capable of producing images of superb quality, including solar and extra-solar planets, as well as the first points of light in the universe. Hey, E.T., E-ELT may be calling for you soon. —TG

Most surfboards were made from polyurethane foam before the main supplier, Clark Foam, ceased operations three years ago. Now several manufacturers are making what they call eco-friendly boards.

But are they any good? To find out, Virginia Tech engineering and science major Michael Porter (right) went on a surfin’ safari last summer that took him to Baja California and up and down the East Coast. Wearing a backpack full of instruments to collect data, he surfed on three different boards, each fitted with strain gauges. Three other students aided the tests, which found good points in each board: One was good in choppy water, another was best for steep drops. But when it came to consistently performing well, all three were a wipeout. The best, nicknamed “Righteous,” could handle most surf conditions but wasn’t good at turns. Porter’s team concluded that not enough careful engineering went into the design of the new boards. —TG

AUSTRALIA—Attracting foreign students is big business for Australian universities. But education experts complain that schools are overdoing the sales pitch, either by stressing pleasure—“sun, surf, and sex,” as one of them put it—or hinting at a fast track to legal immigration. Such marketing schemes may help lower-status schools seeking to increase their income but damage the reputation of prestigious research-oriented universities, say critics, who include Simon Marginson, chairman of higher education at the University of Melbourne, and Michael Gallagher, executive director of the Group of Eight, an association linking some of Australia’s leading research universities.

Now there may be an added reason to stress quality rather than mass appeal: Australia is becoming less attractive financially to foreign students, as other nations in the Asia-Pacific region improve their own educational systems and the strong Australian dollar makes tuition here more costly.—CHRIS PRITCHARD

BELGIUM—Cockroaches may be virtually indestructible, but they’re sure easily fooled. When researchers at the Free University of Brussels built tiny robots that mimic cockroach behavior, the robo-roaches looked nothing like the real thing. But when doused with pheromones that made them smell like cockroaches, the interlopers were quickly accepted into the pests’ society, allowing researchers to study roach behavior.

The Belgian team’s hypothesis was that roaches roam at will but seek out dark shelters where there are other roaches when they want to rest. In an experiment, they gave the roaches two shelters to choose from: one dark and one light. The robots were programmed to pick the dark one. Sure enough, the real roaches congregated in the dark one, as well.

But when the team reversed course and directed the robots to the lighted shelter, the real roaches followed. Bottom-line finding: A few strong-willed individuals can greatly alter the behavior of an entire roach community.

Now, if only those robots could lead the way into roach traps. —TG

When the world’s fastest supercomputers were ranked last November at www.top500.org, BlueGene/L, the IBM machine at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California was still reigning champion. Thanks to a recent upgrade, it now reaches the breakneck speed of 478.2 teraflops—a teraflop being a trillion calculations per second. But BlueGene/L won’t remain No. 1 for long. By early 2009, a new generation of supercomputers will leave it in the dust. These turbocharged machines will perform at least a quadrillion (1,000 trillion)—calculations per second. That speed is called 1 petaflop, and it’s more than twice the rate of BlueGene/L. One contender for the first petaflop computer is Roadrunner, being built by IBM for DOE’s Los Alamos National Laboratory. It will use souped-up versions of the Cell processors found in Sony PlayStation 3 consoles. Another contender is the Cray supercomputer, code-named Baker, destined for the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Livermore also expects to have an IBM petaflop machine by 2010, and the National Science Foundation is bankrolling an IBM petaflopper, Blue Waters, to be housed at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Researchers say petascale machines—which cost around $200 million—are needed to crunch the amazing amounts of scientific, medical, technical, and military data collected by powerful telescopes, climate satellites, and gene analyzers. The massive computational power of these supercomputers will enable scientists to create simulations that can speed drug development, improve weather and climate-change predictions, develop new materials, and help us understand the evolution of the galaxies. Petascale supercomputers will eventually give way to true monsters: the exascale supercomputers capable of handling a jaw-dropping million trillion calculations per second. —TG

Walter H.G. Lewin doesn’t seem all that surprised that he’s become a sought-after celebrity. But then, as a physicist, the 71-year-old professor understands chaos theory, which posits that seemingly small occurrences can cause large and unpredictable events.

For years, Lewin’s inspired, prop-laden lectures—each a product of 40 hours’ work—made him a favorite at MIT. To demonstrate rocket power, for example, he rides a tricycle fueled by a fire extinguisher. Yet when the school began posting videos of his lectures at its public OpenCourseWare website, Lewin’s academic antics and natural showmanship gained him fans across the globe. Retirees even sent e-mails claiming he had helped them overcome depression. After the New York Times featured him on Page One, his fame skyrocketed. Prism caught up with Lewin as he was discussing a possible book project and arranging to appear on late-night TV.

Lewin says he is gratified to popularize physics and science, but that “I never anticipated they would change people’s lives.” Teaching has “always been my love,” says the Netherlands native, who started at MIT in 1966. For that reason, he tries to ensure that every lecture is a “masterpiece.” Ninety-four of them are now posted

online. —TG

BRITAIN—It looks like an ordinary adhesive bandage, but a device developed by a biomedical engineer at London’s Imperial College is far more complex: It’s actually a disposable, wireless monitor capable of keeping track of key vital signs, including body temperature, heartbeat, respiration, and glucose levels. A small silicon chip inside can process signals received by its monitors and send the data to a cellphone. The data can later be uploaded to a PC, if need be, for further analysis. With the device, patients could be monitored around-the-clock while at home, thus shortening hospital stays.

Christofer Toumazou, who developed the technology, also created a new ultralow-power protocol, called Sensium, to transmit the data,using a low-cost, printable battery that can last five days.

If all goes well in clinical trials, the new device will be marketed to healthcare professionals. Their acceptance will be important in showing that the data are trustworthy, says Keith Errey, who together with Toumazou founded Toumaz Technology to market the device. Eventually, Toumaz aims to make a version for athletes. Perspiration is no sweat. The monitor’s waterproof. —TG

Like the rest of the country, California faces a serious shortage of engineers in the coming years—as many as 40,000 workers. Late last year, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger announced several solutions, including expedited university certification for veterans with engineering experience; $1 million in funds for community college-industry apprenticeships; the launching of an Engineering Education Council; and the expansion of High Tech High, an engineering-focused charter school program. It all sounded great. But in January, Schwarzengger proposed drastic 2008-9 budget cuts to counter the state’s anticipated $14.5 billion deficit. With a reduction of more than $1.1 billion in funding, California’s public universities and colleges may now have to turn to such measures as hiring freezes, enrollment limitations, and raised fees. Will Schwarzenegger prove to be the savior of engineering education or the terminator?—Robin Tatu

Some 2 billion people in the developing world have no access to electrical power and light. They rely instead on jury-rigged kerosene lamps, candles, traditional battery-powered flashlights and wood or manure fires. Effects include risks to health and safety from fires and toxic fumes; poor security, pollution from burning kerosene, and deforestation—not to mention the difficulty faced by schoolchildren trying to study at night. Now two U.S. companies have devised novel ways to illuminate these dark corners:

The lack of nighttime lighting stunned—and inspired—Mark Bent when he visited a rural Eritrean village two years ago. A former Marine and U.S. diplomat who has worked in Angola, Bosnia, and Somalia, Bent began pondering a solution. The result is a durable, solar-powered LED flashlight, called BoGo. Manufactured in China, it uses nickel-cadmium batteries to convert sunlight to power. It takes 10 hours to charge and provides five hours of light. Bent quit his job as an oil executive to start SunNight Solar in Houston, which sells the flashlights for $25. For each one sold, SunNight provides another one gratis to a recognized charity operating in the developing world. Hence the name, BoGo: buy one-give one. The United Nations recently purchased 10,000. A new design will make the BoGo waterproof and able to light a room.

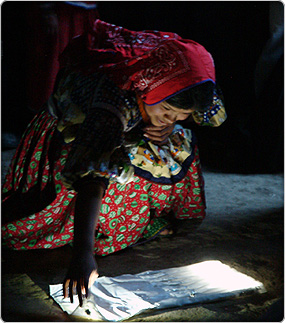

Boston’s Kennedy & Violich Architecture has created Portable Light, a cloth bag with indium gallium diselenide solar cells woven into the fabric. During the day, the cells—made by Global Solar Energy of Tucson—capture energy from sunlight and store it in small lithium-ion batteries. At night, the batteries power hundreds of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) that are also sewn into the bags’ material. When the bag’s spread out, it can provide background light for a room. Roll the bag up, and the light can focus like a flashlight’s spotlight. Three hours of sunlight can produce 10 hours of night light. The first recipients of the Portable Light bags will be the Huichol Indians of Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains (right). While the $50 cost of the bags is not cheap, given that many of the rural poor already spend $10 a month on kerosene, candles, and short-lived dry-cell batteries, it could be a bright investment.—TG

Later this year, it’s quite possible that an entirely new life-form will come into existence. And it will be man-made. Synthetic Genomics was launched last June in Rockville, Md., with $31 million from investors—and is run by J. Craig Venter, the controversial scientist who sped the mapping of the human genome. It has already created the first synthesized chromosome, one long strand of DNA that will be planted into the cell of a simple bacteria, kick-starting it to life. Other companies, like DuPont, are similarly racing to create simple but new life-forms.

Syntheticbiology.org, an online forum hosted by researchers involved in the new technology, states that it is “fundamentally an engineering application of biological science.” The researchers foresee its application in the creation of microbes that have a single purpose, noting that fully synthesized organisms are more easily manipulated.

Venter’s company, for example, wants its progeny to produce clean fuels, like ethanol and hydrogen. Some pundits have already nicknamed them—what else?—frankenfuels. New drugs and ways to clean up industrial spills are other potential applications. Yet synthetic biology raises ethical questions, as well as issues of safety, security, and patent rights. The notion of tailor-made bioweapons in the hands of terrorists is a sobering thought, indeed. Syntheticbiology.org acknowledges the risks but says the potential benefits justify continued ethical research and development. —TG

American engineering requires a substantial upgrade in all aspects, ranging from how it’s taught to how it’s practiced, according to a 131-page “roadmap” for the profession by James J. Duderstadt, emeritus professor at the University of Michigan.

“To compete with talented engineers in other nations with far greater numbers and with far lower wage structures,” Duderstadt writes in Engineering for a Changing World, “American engineers must be able to add significantly more value than their counterparts abroad through their greater intellectual span, their capacity to innovate, their entrepreneurial zeal, and their ability to address the grand challenges facing our world.”

Drawing on a number of recent studies, Duderstadt concludes that engineers need a boost in status and influence.

But for that to happen, engineering education should follow the lead of “all other learned professions” and be pursued at the post-graduate level after students first acquire a “broad liberal arts baccalaureate education.” At the same time, engineering and technology should become part of undergraduate education. Research, he maintains, should be redefined and directed toward “compelling social priorities.”

A “guild-like culture” ought to be developed, similar to that in medicine and law, in which engineers come to identify themselves as part of a unique profession, rather than as employees of a company. Licensing requirements may have to be changed to make sure engineers continue learning throughout their careers, states Duderstadt.

In addition, everyone involved in the profession needs to be committed to giving engineering “a racial, ethnic, and gender diversity consistent with the American population.” —TG

Category: Briefings