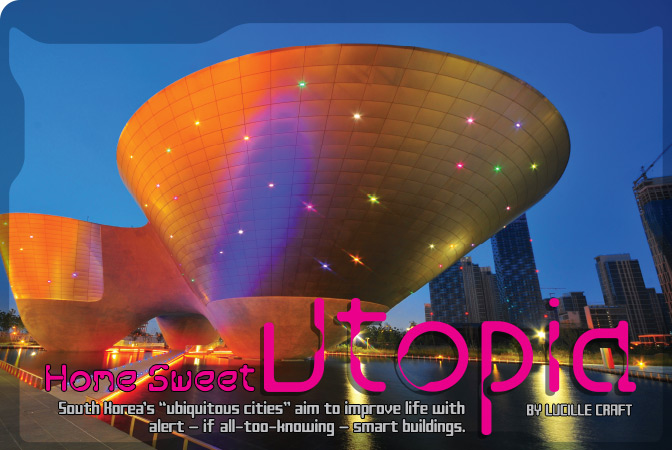

Home Sweet Utopia

SEOUL — With his athletic build and snappy letter jacket, Dong-Hwan Lee could pass for a linebacker, but he makes no claim to football prowess. “For $35,” admits the SungKyunKwan University graduate student, “anyone can buy this jacket!” Lee’s real preoccupation is a tricked-out skywalk near his lab that connects two buildings within the engineering department. The cylindrical, stainless-steel-and-tempered-glass passageway contains an elaborate system of embedded accelerometers, strain gauges, tilt meters, thermo-hygrometers, carbon dioxide detectors, kata thermometers, and wind and motion sensors — not to mention GPS and CCTV cameras. As unsuspecting visitors stroll through this trellis of high-tech tools, details about wear and tear and climate conditions are silently monitored at Lee’s desk or on his smartphone.

At another carrel, fellow grad student Ki-Cheol Kim trains his sights on the lab itself. He measures the level of carbon dioxide in the room while monitoring his classmates via remote camera to see how and when they nod off at their seats. If spikes in CO2 are the culprit, it might be time to crack the windows.

Imagine living in an environment designed to promote the health, happiness, and safety of residents, where no one had to wait in the rain for a bus or breathe polluted air. That’s the vision behind “ubiquitous cities,” one of South Korea’s hottest engineering fields. Pioneered by an elite cluster of universities that include SungKyunKwan (SKKU) and its new Department of u-City Design and Engineering, the field is drawing talented students like Lee and Kim with its mix of architecture, technology, and green design. The concept is simple: By outfitting communities with radio frequency identification devices, sensors, smart-card and videoconferencing systems, and other hardware, u-cities promise improvements in administrative efficiency, public health, traffic management, disaster response, education, security, sustainability, and convenience. In short, u-topia.

So-called smart cities have been evolving around the world for years. Yonsei University graduate school of information’s Jung-hoon Lee, who studies intelligent cities, reckons there are a total of 143 such urban outposts. But in the quest for high-wired efficiency, perhaps nowhere else are the tail winds quite as ferocious as in Asia’s fourth-largest economy. Korea’s u-city boom is uniquely government driven, notes Lee. “Changing cities is not easy using a bottom-up approach, unless there’s heavy investment. Ours is more of a big bang.”

At first glance, SKKU seems a surprising hub for the u-city explosion. Founded in the historic city of Suwon six centuries ago as a place of Confucian learning, the school lie a few miles from the well-preserved ruins of a Choson imperial fortress. Like just about everything else in this booming metropolis south of Seoul, however, the campus has plunged headlong into cyberspace. Suwon, a city of about 1 million people that has invested heavily in becoming a high-tech industrial hub, is home to Samsung Electronics, the world’s top technology company by revenue, whose parent, the Samsung Group, also owns the university.

This industrial connection gives SKKU a natural edge in developing ubiquitous-cities programs: Like most South Korean universities, it combines architecture and engineering in a single department. That makes it easier to pool expertise from a variety of fields. “To make a u-city requires multidisciplinary theories and principles,” explains Cheol-Soo Park, an associate professor in SKKU’s u-City department. “It involves so many theories and design aspects.” U-city students, for example, typically hold degrees in civil engineering, computer science, or architectural engineering. SKKU offers them four subspecialties in “green” engineering: u-city planning, infrastructure engineering, construction management, and green facility management

World’s Most Wired

What’s going on at SKKU is a microcosm of the race nationwide to connect citizens with the buildings and infrastructure they inhabit. “Ubiquitous computing,” wrote Jong-Sung Hwang, now assistant mayor of Seoul, “infuses computers into the real world and renders the distinction between the real and the virtual world meaningless.”

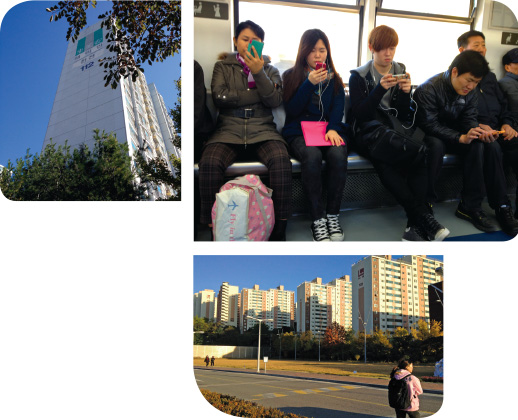

Inspired by the late computer scientist Mark Weiser, deemed the “father of ubiquitous computing,” South Korea is trying to brand itself as the mecca for u-city design. The country already ranks as the “connection king.” With more wireless subscriptions than inhabitants, it has the world’s highest rate of mobile broadband penetration. That compares with a U.S. rate of 76.1 percent, according to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. At 14.2 megabits per second, South Korea also boasts the world’s highest average connection speed, calculates the quarterly State of the Internet report; the next closest is Japan, at 10.7 Mbps, and Hong Kong at 8.9 Mbps. America trails at 6.7 Mbps.

TOP & BOTTOM RIGHT: Three-quarters of South Koreans live in cities, often in high-rise apartment megacomplexes. RIGHT: South Koreans like these passengers on a train into Seoul enjoy the fastest, cheapest broadband speeds in the world. PHOTOGRAPHS BY LUCILLE CRAFT

“Korea is trying to find the next growth engine, and we thought convergences were interesting,” says Yonsei’s Lee. One of the most lucrative, it was decided, was melding South Korea’s construction expertise with its information technology savvy. The Korea Times reports that the country ranks fifth in its share of the world construction market, and second in the information and communication technologies business. The global u-city market is valued at $240.8 billion.

No fewer than 28 u-cities are on the drawing board in South Korea, which does not include retrofitting of existing urban centers like the capital city of Seoul and Busan, Korea’s second-largest metropolis. Embedded sensors are now standard on major construction projects, says SKKU’s Park, as are browser-capable wall pads in new apartments. Making buildings smart, Professor Lee reckons, adds about 10 percent to the cost of the structure.

Of the u-cities started from scratch, the most famous internationally is an ambitious development known as Songdo, located on 1,500 acres of land reclaimed from the Yellow Sea, in the city of Incheon. Unlike Suwon, Songdo is a private-sector joint venture between Posco Steel and U.S. developer Gale International. Envisioned as a “multifunctional oasis,” Songdo includes the country’s first salt water canal and its own Manhattan-like green space, called Central Park. But the project, while moving ahead slowly, remains half-finished. Detractors make unflattering comparisons to planned-city debacles like Brasilia. “Incheon expected foreigners to rent the buildings, but it failed to attract them,” says Professor Park. “Songdo is an example of failure.”

But Yonsei’s Professor Lee argues that Songdo will eventually, if belatedly, make good on its pitch to become a tech showplace and global center to match Singapore or Hong Kong. Meanwhile, a smaller-scale community geared exclusively to the domestic market, called Gwanggyo u-city, is rising on what used to be four square miles of rice paddies in Suwon city. It will house about 77,500 residents, and Park says it’s on target to be in the black within five years. The city will have its own optical fiber-cable network, connecting the operations center with government buildings and emergency services. Sensor-saturated buildings and physical structures will allow remote monitoring of bridges, sewage plants, and water quality, giving managers the means to zero in on trouble – be it icy roads, broken lights, or air pollution – and fix it fast.

Yujin Robot’s Cafero, a drink-serving robotic waiter, takes and delivers orders at the Robot Café in Sondo u-city. © TOPIC PHOTO AGENCY/CORBISE

If u-cities deliver on what boosters promise, municipal services such as obtaining a copy of a birth certificate would become much like stopping at an ATM. Kiosks in neighborhoods throughout the city would offer 24/7 instant access to legal documents. Instead of lining up at the bus stop and being forced to wait no matter what the weather, passengers could simply check exactly when boarding will begin, based on real-time traffic conditions and the bus’s own GPS coordinates – and repair to a coffee shop. Sensor-equipped theater seats would let moviegoers know if there were tickets left for their favorite flick.

Fanciful accounts in the Korea Times talk about 70 becoming the new 50 in a u-city world where nano-robots would automatically filter your bloodstream while keeping your doctor apprised of your vital signs. In this brave new world, elevators won’t need buttons anymore; thanks to RFID tags, a resident could simply step in and sensors will “read” and whisk him to his floor, or direct him to the spot where he left his car in the parking garage. The same technology could coax drivers into leaving their cars at home by awarding redeemable eco-points. RFID tags plus CCTV will offer constant anticrime monitoring – although Park mourns the fact that their budget in Suwon won’t allow for “smart” camera monitoring that can detect suspicious movements.

Could u-cities catch on in other parts of the world? Americans, accustomed to sprawling homes and large yards, might shun unrelenting blocks of 40-story concrete high-rises. But in a densely populated nation like South Korea, where three quarters of its 50 million people live in crowded cities and skyscrapers have become the modern home sweet home, the concept seems tailor made. Seoul alone has about 3,000 skyscrapers; only Hong Kong, New York, and a few other cities have more. The proliferation of megablocks – which designers have spruced up in a lively departure from the grim uniformity of older buildings — has made outfitting residents with state-of-the-art telecommunications relatively cheap. In Suwon city, boasts SKKU’s Park, “I can download a movie in a minute!”

For Americans, the constant and intense monitoring of u-cities residents might conjure up a privacy nightmare from George Orwell’s 1984. But Koreans regard their wired society as inevitable in a country that runs on prodigious amounts of caffeine and where bali bali (fast-paced and stressful) defines the work ethic. “We like quickness,” says Cheol-Soo Park. For better or worse, South Koreans are happily hurtling into the cyberfuture, serving as guinea pigs for the kinds of cities we all may one day inhabit.

Lucille Craft is a freelance journalist based in Tokyo.

PHOTO AT TOP: ROBERT KOEHLER/GETTY IMAGES

Category: Features