Harvard Turns a Corner

On a warm, sunny afternoon in September, 2007, Harvard did something it hadn’t done in more than 70 years: It opened a new school. The Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (HSEAS) was formally christened at a ceremony held on the lawn of Pierce Hall, attended by several hundred faculty and visiting dignitaries from industry and educational institutions across the country, including the deans of engineering at Princeton and nearby Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “As we dedicate our new School we affirm the vital importance of engineering and the applied sciences as part of the Harvard academic enterprise,” Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust said. “And at the same time, we affirm their power to connect, to bridge, and therefore to enliven and strengthen a great many other parts of the university, as well.”

The elevation of engineering at Harvard from a division to a school represents much more than a simple switch of names. “As a school within Arts and Sciences, we will still have Harvard undergraduates who choose engineering as a concentration as opposed to a separate engineering admittance. We will still give graduate degrees through the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences,” said Provost Steven Hyman. “But that said, the school will have substantially more administrative independence than it had. It will also be more in charge of its economic affairs, as well.” Hyman foresees more collaboration in the future, not only within Arts and Sciences, but also between Engineering and other important Harvard schools, including Medicine and Business.

The opening of the new school preceded by several months another, more publicized change at Harvard: the university’s decision in December 2007 to raise substantially the income ceiling on financial aid. Starting this fall, undergraduates from families with incomes of up to $180,000 won’t have to pay more than 10 percent of the family’s income in school costs.

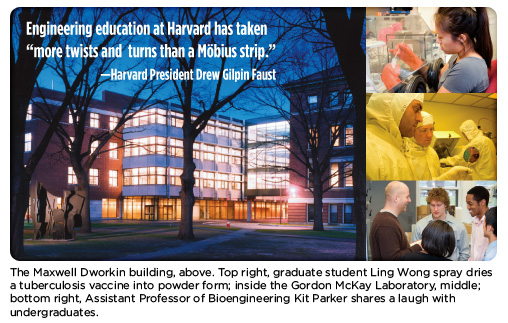

Part of the impetus for the new school came from two of Harvard’s most prominent former students, Microsoft founder Bill Gates and company CEO Steve Ballmer. In 1996, the two men donated $25 million to Harvard to create the Maxwell Dworkin building for computer science, named after their mothers, Mary Maxwell Gates and Beatrice Dworkin Ballmer. At the time, the pair pressed Harvard to place more emphasis on computer science and electrical engineering. They also suggested hiring a dean who understands engineering and applied sciences. Two years later, Venkatesh Narayanamurti—“Venky” to friends and colleagues—was recruited from the University of California at Santa Barbara and began the task of raising Harvard’s engineering profile.

Right from the start, Narayanamurti says he recognized that in addition to computer science and electrical engineering, Harvard had an opportunity to add an important third leg: “Boston is the hub of a lot of life sciences, as well as the home of Harvard’s Medical School, so there was a tremendous opportunity in bioengineering, as well.” He adds, “I went before the overseers and the corporation several times. Things move slowly. We finally got approval from the faculty of Arts and Sciences last December and then from the corporation formally in February 2007. It was a six- or seven-year effort with a lot of support from a lot of people.”

Narayanamurti’s pivotal role in the elevation of engineering to a school status drew praise from Faust at the opening ceremonies. Referring to him as “the North Star of our engineering galaxy,” the president said that it was his “foresight, determination and energy we have to thank for the milestone that brings us together today.”

A Tangled History

Engineering education has a long, convoluted history at Harvard—“more twists and turns than a Möbius strip,” says Faust. It began formally in 1847 with a gift of $50,000 from Massachusetts industrialist and entrepreneur Abbott Lawrence. After a promising beginning, the Lawrence Scientific School struggled in the late 19th century. President Charles William Eliot, who helped establish Harvard as a premier American institution during his 40-year stewardship, regarded practical education with condescension, despite his training as a chemist. Computer science professor and former dean of Harvard College Harry Lewis notes in his book Education Without a Soul: Does Liberal Education Have a Future? that engineering was important to Eliot, but “it was for boys who did not have the ‘makings’ of a preacher or a scholar. It was not the sort of boy who went to Harvard.”

Eliot did his best to rid Harvard of the Lawrence Scientific School, three times offering it to MIT, where Eliot had taught and where he believed engineering education better resided. A fourth attempt by Eliot’s successor, A. Lawrence Lowell, precipitated a court battle that went all the way to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The case centered upon a claim by the trustees of a huge 1891 endowment entrusted to Harvard by industrialist Gordon McKay, which specifically stipulated that Harvard would continue to offer an engineering program. McKay had been advised to give his money to MIT but chose Harvard because it offered an education more compatible with his vision of the cultured engineer—someone in the tradition of Leonardo da Vinci. By proposing that MIT assume the teaching of Harvard’s engineering courses, the college was reneging on its agreement with McKay, the trustees charged. In 1917, the court ruled against Harvard’s proposal and the following year, engineering education was reinstated at the university.

Since then, Harvard’s engineering and applied sciences have undergone a raft of name changes, including the Department of Engineering Science, the Department of Engineering Sciences and Applied Physics, the Division of Applied Science, and the Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

The birth of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences in 2007 means that “the wheel is now coming full circle,” Narayanamurti said in his address at the school’s opening. “The Lawrence School is being reborn, in a form and mission appropriate for the 21st century—rooted in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences; nimble and interdisciplinary; connected to Harvard’s great professional schools; and directed toward discovery, innovation and impact on society.”

Some say this change should have taken place long ago. Charles M. Vest, president of the National Academy of Engineering and president emeritus of MIT, jokingly borrowed a line that Winston Churchill once used to describe Americans. “Harvard always does the right thing,” Vest said in his keynote address at HSEAS’s opening, “after it has exhausted all the other possibilities.” Lewis agrees that there’s truth to the statement, particularly as it applies to engineering. But now, “many feel that Harvard finally has ‘got it,’ and that the school understands that it cannot be a great research university without a great engineering program.”

Narayanamurti is convinced that the new school will improve not only the quality of engineering education but also the caliber of students it attracts. “In Harvard parlance, a school has a lot of stature. We are now a visible part of Harvard—not hidden. We always had great professors and great students, but now it is recognized as an important discipline—or disciplines.” He foresees engineering growing in the next five years to what he terms a “medium-size school”—roughly 100 full-time faculty, up from the current 70—“not too large, but large enough to have critical mass in certain areas.” He adds that neighboring MIT, a school he greatly admires, will always be larger than Harvard in engineering. And “if you really want to be a techie, you are better off going to MIT because they are much stronger. But in certain other areas we will have an advantage.” Indeed, pointing to the number of distinguished social scientists and humanists at Harvard, Narayanamurti suggests that exposure to such an array of talent contributes to a well-rounded graduate at a time when barriers between disciplines are dissolving.

Renaissance Environment

For Eric Lieberman, who earned a master’s degree in history and manuscript studies before coming to HSEAS, Harvard’s Renaissance environment was a big draw: “I’ve taken several classes in history and at the Divinity School while here,” he says. “It’s great.”

Biomedical engineering major Laura Chin agrees. A member of the Harvard Early Music Society who rejoined the engineering program after a semester in Paris, Chin says that the range of instruction “facilitates an open-mindedness and innovation that would not exist for me in a more narrowly focused environment.” She also believes that HSEAS will help Harvard keep abreast of technological developments, noting that a separate engineering school “ideally maintains direction, ambition and innovation, but gains autonomy and a greater capacity for adaptation.”

For Narayanamurti, engineering is a core ingredient of a well-rounded education: “I have always thought that an undergraduate cannot be broadly educated unless he or she has an appreciation for technology.” He adds that the fact that Harvard has produced leaders who end up in Washington—including seven U.S. presidents—underscores the need to ensure that others, not just engineers, learn about technology and its role in the country’s future: “Technology is no longer a niche activity.”

Others also believe that the change will be felt beyond Harvard’s ivy walls. “Harvard’s action will resonate throughout academia, particularly in providing impetus for other institutions to rethink the role of engineering in the context of a liberal arts,” says Vincent Poor, dean of engineering at Princeton. Lewis agrees: “Everybody wins when there is strong competition for students, faculty and research funds. Everyone has to be a little better. We’ll get a little better, they’ll get a little better. There are such great opportunities in the Boston area for cooperation, as well as competition. We already have a cross-registration with MIT. Maybe in the future a few more of the buses will be coming from East Cambridge (MIT) to West Cambridge (Harvard).”

Pierre Home-Douglas is a freelance writer based in Montreal.

Category: Features