JAPAN’S SLOW-MOVING TIDE

BY LUCILLE CRAFT

TOKYO

Professor Tsuneo Kinoshita holds court in a windowless cubicle that somehow manages to accommodate a clutter of desks, chairs, whiteboards and laptops, not to mention the soft-spoken electrical engineer himself and his seven students. The class is debating whether to tackle a rather intimidating new project—redesigning a cell phone for mobile computing—and whether this Linux-based marvel can be whipped into shape in time for the college’s annual show-and-tell.

The classroom is stifling, the semi-darkness soporific and the genial professor’s presentation decidedly bumpy, Mr. Bean with a PowerPoint. He laboriously switches between Japanese and English, compulsively mopping his brow as he struggles to locate the right translation in his second language for the benefit of two exchange students from Paris. The scene, on the 17th floor of a downtown skyscraper occupied by Tokyo’s Kogakuin University (KU), was reminiscent of an international business meeting, right before the frustrated participants yell, “Get us an interpreter!”

And yet, if the linguistic speed bumps are painfully obvious, no one seems to care. The nuts and bolts of building a pocket PC rivets the French students, whose own country seems quaint compared to the broadband boom they are witnessing in Asia. And after a few minutes, it becomes clear that the assembly has become adept at decoding each other’s intentions. Gilles Darliguelongue, a lanky 21-year-old, rarely speaks except whispered conversation in French to the other Parisian student, but he occasionally stretches an oversized hand to the whiteboard, scribbling out diagrams whenever he wants to “say” something.

“We understand the main ideas but not the details,” says Darlinguelongue, who confesses his Japanese ability is rudimentary. “But we have to adapt to the experience.” His Japanese classmates, meanwhile, are in the same boat, comprehending roughly half of the English spoken in the room, which is why they rely on the professor for translations.

“This is like a dream come true for me,” says Darlinguelongue’s classmate Aurelien Tran, 23, who is studying at KU for a few months under an exchange with his alma mater, the Ecole Superieure d’Ingenieurs en Electronique et Electrotechnique. For him, Japan is the mecca of microelectronics. Mingling with Japanese students and attending classes, he says he “can see the Japanese way of thinking.” Japanese students might say “mai non,” but the French decide the studious Japanese make their peers back at their prestigious school in Paris look like loafers. The French youths also had high praise for the mentoring relationship Asian scholars tend to adopt with their students, in contrast to the aloof pose struck by their own professors back home.

A Japanese senior, recently back from a three-month sojourn at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, Calif., found the journey equally enlightening. “I was very shocked,” she said. “I (had always) thought studying by myself is the best way to study, but (I discovered that) sometimes I need someone else’s help to get a brand new idea.”

Kogakuin—literally, “engineering institute”—is at the forefront of the movement within just a handful of Japan’s engineering schools to better prepare their graduates for a world where understanding foreign markets and mores has shifted from elective to prerequisite. This spring, KU unveiled Japan’s first Faculty of Global Engineering with 75 students. The global engineer major leavens the usual technical courses with a hefty dose of classes in world history, global business and, of course, English. The Japanese students will end up spending up to three months working on a collaborative project with peers at Harvey Mudd; and KU is aggressively recruiting overseas to ensure there are always three or four foreign students on campus. (There apparently is no shortage of candidates, since studying here offers the alluring prospect of bagging a job with a Japanese electronics company after graduation; but many foreign students are deterred by the high cost that studying in Japan entails.)

The man behind KU’s global engineering faculty is its dean, Okitsugu “Oki” Furuya, who proselytizes tirelessly, in person and in his recent book, “Global Engineer.” Not long ago, companies assumed the burden for tutoring employees on how to function in a global economy, he says. “Universities said, ‘To hell with that—it’s not our job!’ ” But from his own experience working as an expat engineer in the United States, wincing as Japanese colleagues floundered in overseas business meetings, and after conversations with acquaintances at Japanese electronics makers, he became convinced conventional engineering courses are no longer delivering the goods. “I heard from Toyota, Honda and Toshiba that they don’t have enough engineers to go to China, or wherever,” he says.

Furuya had his work cut out for him when he set out to create a global curriculum almost a decade ago. “In Japan, we say engineers are people who become engineers because they’re not good at English!” But curing his charges’ lingua-phobia is only one hurdle, Furuya says, realizing that his primary role was equipping his students with the agility to survive and thrive in any culture.

Dragging Japanese engineering curricula into the global era is no mean feat. As much as Japanese universities adore the imprimatur of “collaborations” with foreign universities, many of these arrangements never live up to their promise. “We think about globalization a lot, but in Japan, it’s mostly just lip service,” says Shuichi Fukuda, of Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Technology. Like its silver-haired owner, Fukuda’s office is a mixture of inspiration and deprecation: a copy of Murphy’s Law, a Dilbert poster and a University of Missouri pennant. He literally emits steam, fulminating over how China and South Korea send legions of students abroad for training while precious few Japanese students go overseas—a rational choice, since Japanese employers tend to favor grads with local sheepskins.

Foreign students, and of course foreign professors, are rare in Japanese engineering. That is ironic, Fukuda notes, because of all the disciplines a university offers, engineering probably has the lowest barriers to entry for those with limited or nonexistent Japanese language skills: Because of the preponderance of universally understood symbols and concepts, even the most English-challenged Japanese student can usually negotiate writing and reading in English. Very few Japanese professors, on the other hand, feel confident teaching in English, Fukuda says, effectively barring Japanese universities to all but the rare engineering exchange student who can get by, like Chinese or Korean students who can at least comprehend the Chinese-based Japanese writing system. The Byzantine infrastructure, tightly regulated and budgeted nature of most Japanese universities makes it difficult to hire foreign professors, even on a visiting basis. The relatively impenetrable nature of Japanese academe—Science Council of Japan President Kiyoshi Kurokawa, speaking at the recent World Economic Forum in Tokyo, branded Japanese institutions as “sakoku,” or closed fortresses—stands in stark contrast to Singapore, which sees foreign teachers and students as vital to its very existence as a competitive economy. “Our philosophy,” said Tan Chin-Nam, permanent secretary, ministry of information, Singapore, at a recent World Economic Forum in Tokyo, “is that if we cannot produce enough babies ourselves, we’ll borrow other people’s babies!”

Taking the Initiative

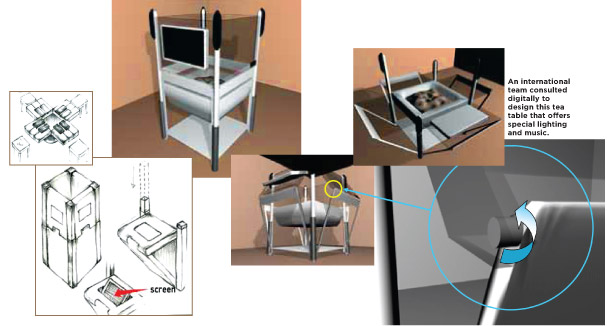

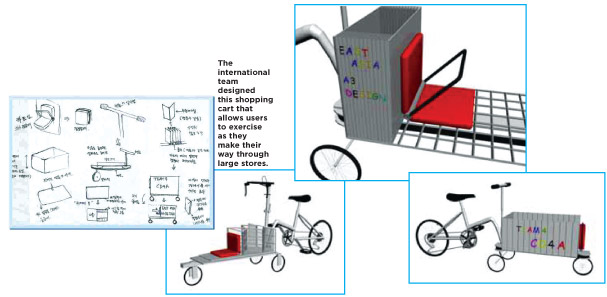

Frustrated with foot-dragging at their institutions, professors like Fukuda have recently begun carving out global islands within their own turfs, drawing on like-minded acquaintances at foreign schools. Under an ambitious program organized by professor Young Se Kim of Sunkyungkwan University in South Korea in 2005 with professor Shensheng Zhang at China’s Shanghai Jiaotong University—both friends from his days teaching at Stanford—Fukuda arranged to have some of his students join an ambitious international design project. The three countries were represented on each of four teams, which consulted digitally and via teleconferencing, with infrequent face-to-face meetings. Students were graded as a team, by all professors involved; despite the considerable distances in space and culture involved, the students acquitted themselves with panache, inventing a clever ergonomic chair for PC-fatigued users, a table for savoring green tea and a shopping cart that allows the user to exercise while prowling the aisles.

The international project’s success is particularly encouraging at a time when political hostilities among the three countries are at an all-time high, sparked by the Japanese prime minister’s visits to a controversial war shrine. Fukuda fretted about whether the deteriorating political climate would torpedo their project, but these fears proved unfounded. The tri-country program, he says, has proven a refreshing antidote to the poisonous rhetoric and sensational headlines in the newspapers. While issues have arisen over how to finance the project in the future and offer Web-based lectures, the venture has been declared a success both as a design exercise and by teaching students how to thrive in cross-cultural teams.

“Japanese students learned that communication is about a lot more than just words,” Fukuda says. “We just teach them ‘how,’ but never ‘why?’ ” The demand for global engineers is particularly acute in IT, says Hiroshi Fukusaki, executive director of the Japan Accreditation Board for Engineering Education (JABEE). “ Japan wants to retain its competitive edge, especially given the rise of neighbors China and South Korea, and instilling engineers with a global sensibility is seen as key to that aim.”

The unwillingness to promote foreign workers into management and the shortage of globally oriented Japanese engineers even at many blue-chip Japanese companies has real consequences, Fukusaki says. “The most talented engineers in other countries prefer to work for American or European firms. It’s the second-rate engineers who settle for Japanese employers. So Japanese train them as well as they can—and then the ablest end up quitting to work for someone else. Often Japanese firms must send unusually high numbers of staff members to outsourcing locales in order to train these sub-par employees, Fukusaki notes, incurring unnecessarily heavy upfront investments.

“Our people need to be able to understand different markets, customs and cultures,” said Yotaro Kobayashi, chief corporate advisor, Fuji Xerox Co., at a recent seminar sponsored by Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business in Tokyo. Being able to read foreign markets is all the more necessary, he says, because the company has recognized, for instance, the quality demanded by a Japanese customer may not be appropriate in China or India.

“Japanese companies want engineers with communication and leadership skills and the ability to work in teams—and they want universities to instill these qualities,” says JABEE’s Fukusaki. Management skills used to be acquired by osmosis, as an employee typically rotated from R&D, to production, to planning or sales. Sometimes companies even plucked their best engineers out of the rotation to study abroad for a few years. But in the wake of Japan’s punishing, more than decade-long recession, which forced Japanese firms to drastically downsize and adopt “flat” management structures, companies are now demanding new hires hit the ground running, Fukusaki says. At the same time, while demand is surging for IT engineers so much that Japan is easing its traditional barriers to immigration to woo Indian software specialists, Japan isn’t minting engineers at anywhere near the rate it once did. Fukusaki says while overall college enrollments in Japan, the world’s fastest aging nation, are down 20 percent in the past five years, engineering enrollments have sagged at twice the rate—40 percent, as students opt instead to major in the comparatively less-demanding and more lucrative fields of business or finance.

“Professors are like children!” fulminates Makoto “Mac” Yoshida, who’s an expert on network management “queuing theory” from telecom giant NTT who was drafted to help modernize the engineering department at University of Tokyo, Japan’s Harvard. “Ph.D.’s have no experience in the private sector. They’re always in the lab, always want to work with the same people.” This arrangement worked well until as recently as the past decade, when Japanese companies happily accepted students into research departments. These recruits needed neither “people” skills nor foreign language ability.

But the advent of the Internet meant that development cycles have become brutally short—and staffs, brutally small. “Almost all of Toyota’s components are now made overseas,” Yoshida grimly notes. “So we need engineers who can manage” these offshore factories.

Japan ’s postwar miracle was built on exports, and the Japanese have no shortage of experience in selling and sourcing in overseas countries. But the contrast between the demands of the recent past and today is like comparing schooners and container ships. “We used to deal only in physical goods,” Yoshida says. “But now we trade in cultures, services and everything else—except politics!” Training Japanese engineers who can negotiate the shallows in any tide, in other words, has become an imperative.

Lucille Craft is a freelance writer based in Japan.

Category: Features